Tall Travel Tales from 17th-Century Mexico, Mapped

Giovanni Careri traveled far and wide, or so he said.

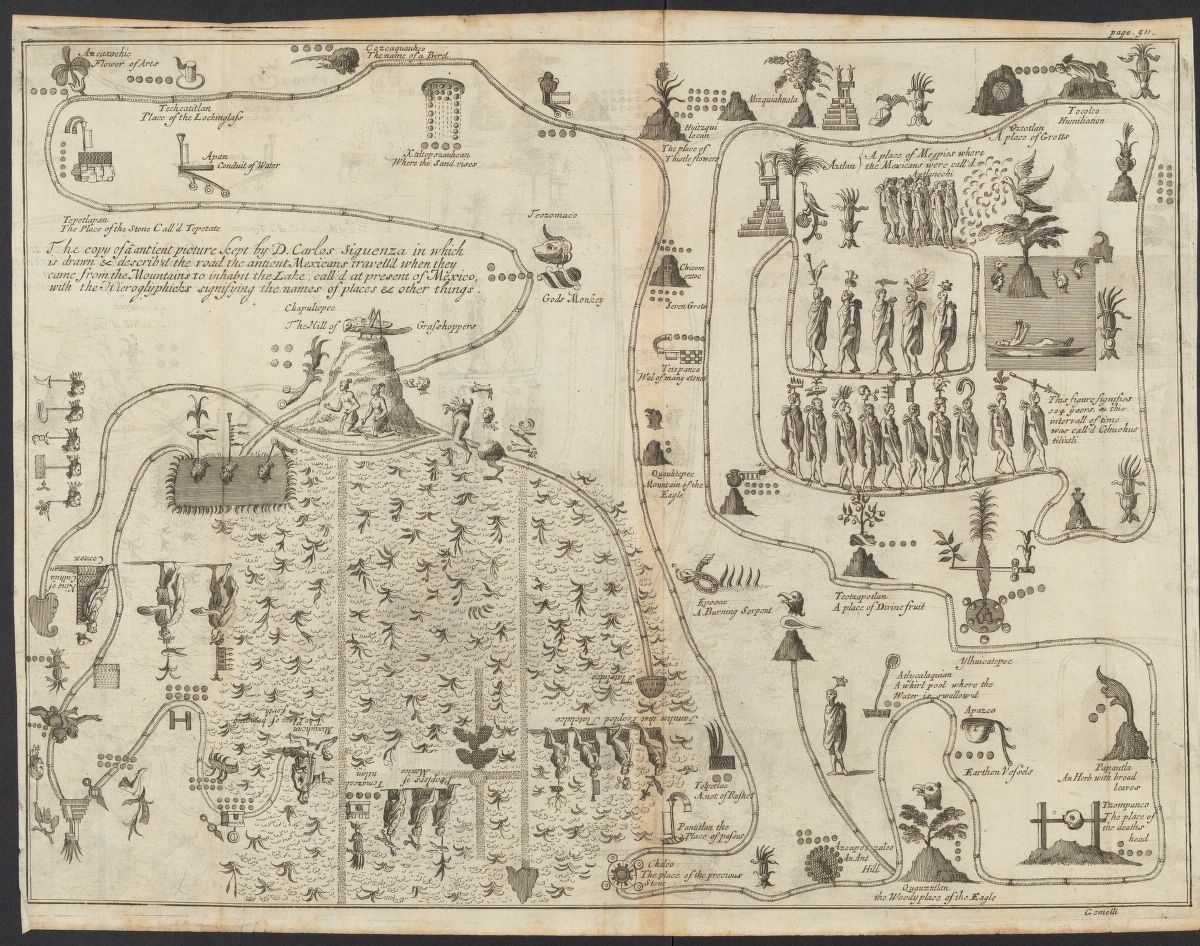

Careri borrowed the map, along with other knowledge, from New Spain local Don Carlos de Siguenza. (Image: Harvard Library/Public Domain)

Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri was the original disillusioned lawyer who quit to travel the world.

In A Voyage Round the World (Giro del Mondo), a six-volume set of travel accounts published in 1699 and 1700, the Italian adventurer claims to have visited Persian mints, witnessed fights on the island of Formosa (now Taiwan), and brought two bales of carpets to Indostan. It sounds like an incredible global tour, but there’s no saying how much of his travels he contrived (some have considered them if not entirely, then mostly fictitious).

Either way, Careri, who lived from 1651 to 1725, was a pioneering world traveler among Europeans. He journeyed via merchant ships, not for profit but for leisure and adventure. On a five-year international tour, he voyaged to Egypt, Turkey, and Persia before swinging by India, taking a stroll along the Great Wall of China, then roughing the seas en route to the Philippines and New Spain. Or at least, that’s what we’re led to believe.

A close-up of the map and some of its details. (Image: Harvard Library/Public Domain)

Careri left his cushy job as a lawyer to set off into the horizon, financing his trip largely by buying and reselling items as he went. Did he get passed over for a promotion? Turned down as a partner? Hard to say, but he decided it was time to leave the office and see the world.

One stop along his trip, in 1697, was New Spain, or today’s Mexico, which comprises volume six of his series. Careri’s descriptions of local culture in “New Spain” have been considered among the more convincing of his travel tales; Prussian geographer, Baron Von Humboldt, confirmed that his descriptions of Mexico and Acapulco possessed local charm only achievable through ocular witness.

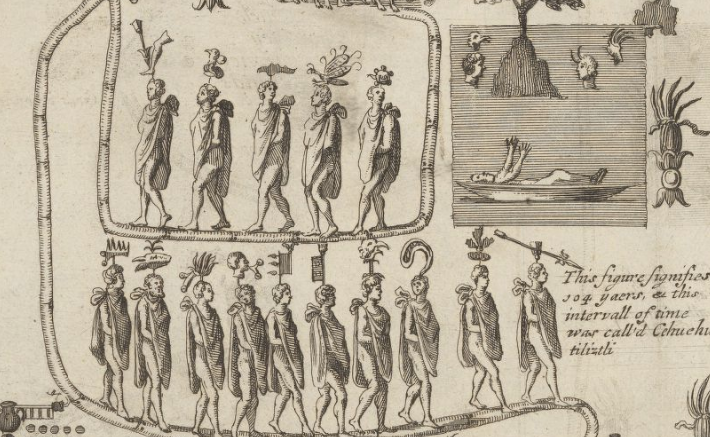

A close-up of the map and some of its details. (Image: Harvard Library/Public Domain)

The map above, copied from the work of Don Carlos de Siguenza, a Spanish intellectual and geographer who spent his life in New Spain, looks more like a board game than an atlas. It seems there should be some instruction somewhere: “You got scurvy: move back five places,” or “You have been named a foreign king: you win the game!” The chunk of script in the upper left gives attribution to Siguenza, who was in contact with Careri, and used him as an avenue through which to publish and disseminate ideas. Careri’s correspondence and consultation with Siguenza during his time in New Spain may have been key in enhancing the volume’s accuracy on the region’s history and customs.

A closer look at the upper right corner of the map. (Image: Harvard Library/Public Domain)

It is less a map, and more an illustrated guide of things one might happen upon along “the road the ancient Mexicans travell’d when they came from the Mountains to inhabit the Lake” in the late 17th century. Such things include: “papantla, an herb with broad leaves”; “tzompanco, the place of the death’s head”; “temazcal titlan”; “Chapultepec, The Hill of Grasshoppers”; “Xaltopozauhcan, where the sand rises”; “atlycalaquian, a whirl pool where the water is swallow’d”; and “Azlan, A place of Megpies where the Mexicans were call’d Aztlanechi”. You’ll have to rotate it to fully appreciate every component of the map’s circumference.

An illustration of the Mexican calendar included in Volume 6 on New Spain. (Image: Harvard Library/Public Domain)

Tucked among his observations about “horrid Sacrifices” and singing nuns, you’ll find the map below. Careri begins his New Spain leg of his around-the-world journey in Acapulco, in what is the last volume of his Travels Round the World. He details the inns and monasteries at which he stays the night, and adds, “As for the city of Acapulco, I think it might more properly be call’d a poor Village of Fishermen, than the chief Mart of the South Sea, and Port for the Voyage to China.” He mentions meager houses of Wood, Mud, and Straw, and natives who he describes as “Blacks and Mulattoes.” Careri reluctantly mentions the city’s few virtues, before delving into the salaries of the King’s curate and port’s chief Magistrate.

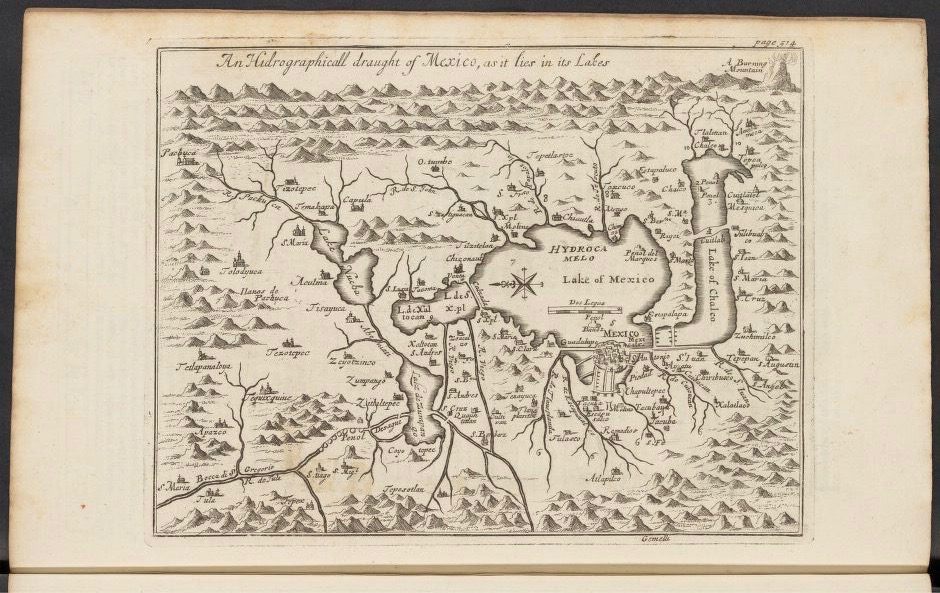

A map of the Lake of Mexico and its environs. (Image: Harvard Library/Public Domain)

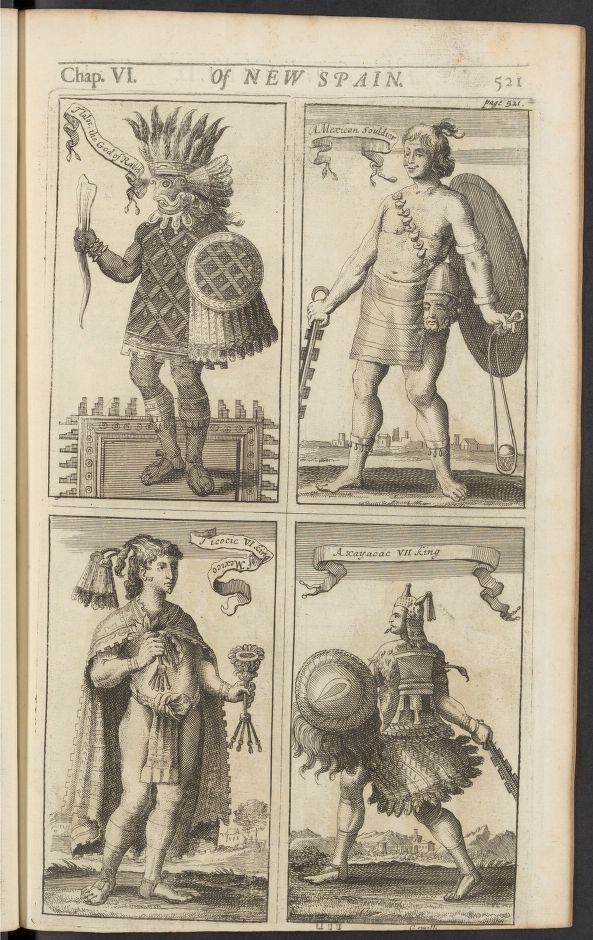

Also included in Careri’s first chapter on New Spain is “An Hidrographicall draught of Mexico, as it lies in its Lakes, closely detailing the mountains the rivers surrounding the Lake of Mexico” (which Careri mentions is courtesy of a “French Ingenier” named Adrian Boot). Later, there are portraits such as that of “Tlaloc, the God of Rain,” “Quauhtimoc X king” and “a Mexican Souldier” (with a decapitated head hanging loosely at his waist).

Portraits from New Spain. (Image: Harvard Library/Public Domain)

Whether or not Careri passed through all the places recounted in his travel memoirs, he is certainly not lacking in detail—names, numbers, dates, arithmetic, geographical bearings, lists of Mexican monarchs, and interesting numerical-alphabetic conversions. One wonders how his publisher’s fact-checking system functioned—but no matter. If you’d like to do your own fact-checking, you can find early editions of all six volumes, or just go straight to the text online, if you have the patience for distinguishing an “s” from an “f”.

Map Monday highlights interesting and unusual cartographic pursuits from around the world and through time. Read more Map Monday posts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook