Dinosaur demise allowed mammals to 'go nuts'

- Published

Land mammals went from small "vermin" to giant beasts in just 25 million years, according to a new study.

Writing in the journal Science, researchers say mammals rapidly filled the "large animal" void left by the dinosaurs' demise 65 million years ago.

They then went from creatures weighing between 3g and 15kg to a hugely diverse group including 17-tonne beasts.

Further growth was capped by temperature and land availability, the scientists believe.

Felisa Smith of the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, US, and colleagues looked at the fossil record of mammals to plot their course through the ages.

They concluded that the rise of the mammals was by no means inevitable, and owes most to the chance obliteration of the dinosaurs, be it by comet, asteroid or another event.

"Mammals actually evolved almost around the same time as dinosaurs, about 210 million years ago," she told BBC News.

"And for the first 140 million years, we were basically vermin scurrying around the feet of the dinosaurs and not really doing much of anything.

"A comet came and hit the Earth and killed off all dinosaurs... and mammals as a class probably had characteristics that helped them survive that impact."

She believes most were burrowers that lived through the ensuing environmental mayhem largely underground, feeding on whatever food they could find, be it plant or meat.

"What came out of that impact at the end of the Cretaceous period was a bunch of really small mammals that were not particularly diverse, probably not much more than a kilo," said Professor Smith.

"But we had a giant Earth with nothing big on it anymore; and so I think that ecological opportunity allowed mammals to just go nuts."

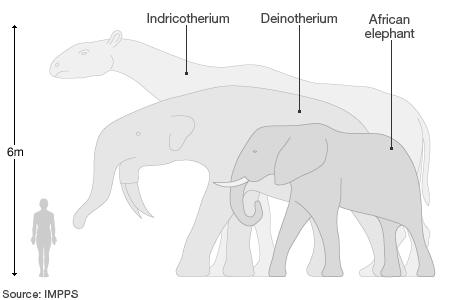

"Going nuts" meant land mammals diverging in shape and size. Some mammals attained weights of 15-17 tonnes, including Indricotherium, a mammal related to horses, and Deinotherium, a member of the elephant family.

They reached these weights within about 25 million years of the demise of the dinosaurs, but weights then plateaued through to recent times, say the researchers.

This pattern was repeated across the continents, they say, suggesting there existed an intrinsic upper ceiling for mammal body mass, probably determined by temperatures and the availability of land.

Larger animals have a reduced surface-to-volume ratio, which makes it harder to dissipate heat - something that warm-blooded creatures must do to regulate their body temperature.

"If you get too big and you're not able to dissipate heat, you can actually suffer; and probably that heat loading was an issue for the very largest mammals," said Professor Smith.

As mammals populated the Earth, reductions in the amount of available land and as a consequence, food, may also have played a key role.

Even so, "mega-sized" land mammals lived on through to just thousands of years ago in the form of the woolly mammoth, which Professor Smith - if not everyone - believes was hunted to extinction by a much smaller mammal, the human.

Professor Adrian Lister of London's Natural History Museum (who believes climate, not humans, killed off the woolly mammoth) said the new research did suggest the existence of an upper ceiling to mammal body mass.

"To demonstrate this parallel feature on all the continents, and that it reached a natural plateau, very strongly suggests some inherent reason," he told the BBC.

"One simple way of reading Darwin is almost anything is possible and animals can be adapted in any way. There's a counter school of thought which says evolution is moulded by physical restrictions too, and that's the most interesting point here."

Dr Kate Jones of the Zoological Society of London, said: "It's a really interesting study, showing some great patterns which we would want to take further using an evolutionary framework."

The new study did not look at aquatic mammals, although the same team is currently preparing a further paper looking at their development through the ages.

- Published17 November 2010

- Published20 January 2010

- Published4 May 2010