Fran Fulton is 66, and she’s been fully blind for about 10 years. A few weeks ago, all that changed.

Fulton suffers from retinitis pigmentosa—a degenerative eye disease that slowly causes light-sensitive cells in the retina to die off. Over the course of several years she lost her sight, and for the past 10 years she hasn’t been able to see anything at all. But in late July, Fulton was outfitted with a system called the Argus II. A pair of camera-equipped glasses are hooked up to electrodes implanted in her eyeball, which feed her brain visual information. Using the system, she can now see the world again. What’s the experience like?

“When they ‘turned me on’ so to speak it was absolutely the most breathtaking experience,” she says. “I was just so overwhelmed and so excited, my heart started beating so fast I had to put my hand on my chest because I thought it was going to pop.”

As both cameras and our understanding of the visual system improve, new techniques to restore sight to the blind are progressing too. Devices like the Argus II are able to bypass damaged eyes to restore some vision to those who have lost it. It’s not the same as fully restored vision, and it’s still in its early days—there are only six people in the U.S. with the Argus II—but researchers hope that as they learn more about vision they can help those who’ve lost it get it back.

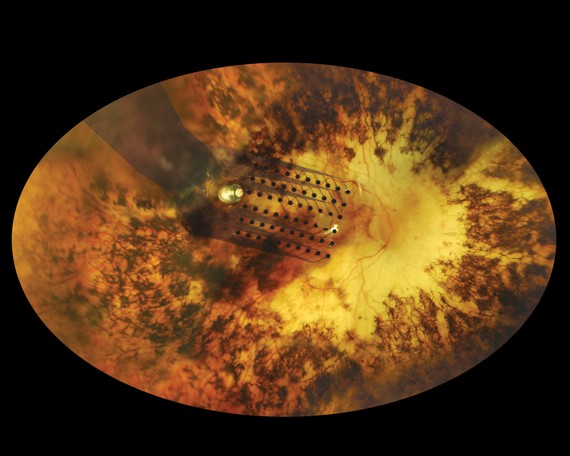

The Argus II system is made up of three parts: a pair of glasses, a converter box, and an electrode array. The glasses aren’t corrective, they are simply a vehicle for the camera—and that camera is no more complicated than the versions found in modern smart phones. The image from the camera is then transmitted down into a converter box that can be carried in a purse or pocket. This box sends signals to the electrode array implanted onto the patient’s retina. Essentially, what the Argus II does is skip over the cells that retinitis pigmentosa has killed to get visual signals to the brain.

Robert Greenberg, the president and CEO of Second Sight, the company that developed Argus II, explains that the eye is like a multi-layer cake. On one layer are the light-sensitive cells, called “rods” and “cones,” that sighted people rely on to take in light and turn that into visual information. But for those with retinitis pigmentosa, those cells are dead. “We’re bypassing those dead cells and going to the next layer of the cake,” Greenberg explains.

This means that Argus II has to convert the information from the camera into signals that the electrodes implanted in the eye can use, and that the brain can interpret. Figuring out how to achieve that was the focus of Greenberg’s PhD thesis. But there was a bigger hurdle to come, he says: working out a way to implant electrodes onto the paper-thin retina inside the eye.

“The retina is like one-ply toilet paper,” he says. “Developing something that can sit on the surface of the retina without damaging it is really difficult. That was tougher than figuring out the algorithms.”

For patients, though, the whole thing is remarkably simple. The surgery to implant the electrodes takes just a few hours and patients go home the same day with an implant that wraps around one of their eyes and is secured by a tiny tack the size of a human hair. After about a week to heal, the patient returns to get the glasses, to have their new electrodes tuned, and to train them on how to use the system. On the converter box there are knobs that let users increase or decrease things like the brightness and contrast. Then they go home with their new pair of eyes.

So what do people using Argus II actually see? Greenberg says it’s best imagined as looking like a pixelated image, or staring at a digital scoreboard held just in front of your eyes. There are regions of light and dark that collectively the brain recognizes as an image.

Fulton, however, says it’s difficult to describe exactly what she sees. “People say you’ll see shapes,” she says. “Well yeah, but it’s the electrical impulses, and it’s about learning how to interpret them. It’s not that it’s hard, it’s just a learning curve. It’s something that I’m learning.”

Fulton says that mostly what she can see is areas of light and dark. She recently had dinner with friends. When they were leaving the restaurant she was able to hone in on a person’s light shirt. “I didn’t need to use a sighted guide, they were in front of me and I just followed them out,” she says. Other patients report that things like fireworks and Christmas trees are especially visible. “I can’t wait for something to happen that I can go to fireworks, I haven’t seen fireworks in a very long time and I am looking forward to that,” Fran says.

Many patients, Fulton included, continue doing vision therapy to improve their sight and train their brain to better interpret the signals.

For Fulton, who works as a disability advocate, getting around now is so much easier. “The first time I left work with it—I work on the third floor and there are three elevators, and I heard the bell to go down. I lined myself up in front of the door and I walked straight in. I didn’t bump my left shoulder, didn’t bump my right shoulder, I didn’t have to use my cane to check. Every day it’s very exciting, and never in my lifetime did I ever think something like this could happen.”

Fulton has long used a cane to detect obstacles in her way, but now her awareness of her surroundings is much more detailed. “I am able to now identify doorways and objects on the street. I can’t tell you whether it’s a flowerpot or a homeless person collecting money, but I can tell you there’s an object there.”

Argus II isn’t perfect: It’s only black and white, for starters. And it’s not like you’re feeding a full image to the brain: Users can’t read signs, or recognise faces, or identify objects—at least, not usually. “I’ve been quite successful at identifying a triangle versus a circle and a square,” Fran boasts.

It’s also important to note that this is not a system that all blind people can use—they have to have an intact retina for the implant to work. Those who lost their site to things like diabetes, glaucoma, or infection and who have damage to the retina can’t use the Argus II system.

Greenberg says Second Sight is working on a new implant that bypasses even the retinal layer, and implants electrodes directly onto the visual region of the brain.

But for those who have been blind for years, simply seeing shapes again is pretty exciting. “I’m very much looking forward to being able to see my grandchildren,” Fulton says. “I won’t be able to see their faces, but I know they’ll have great fun standing in a room and say ‘grandma find me!’ and I’ll be able to tell the difference between the four-year-old and the seven-year-old.”

This post appears courtesy of Tomorrow's Lives, a column from BBC Future.