“I’ve been doing it 24 years now and I couldn’t do it any more,” says Lee Child as he hands over the reins of his Jack Reacher series to his brother Andrew Grant. He’s not the first to tire of his most famous creation. By 1938, Agatha Christie had grown entirely sick of Hercule Poirot, asking: “Why did I ever invent this detestable bombastic, tiresome little creature? Eternally straightening things, eternally boasting, eternally twirling his moustache and tilting his egg-shaped head.” And nearly 50 years earlier, Arthur Conan Doyle was equally wearied by Sherlock Holmes: “I think of slaying Holmes … winding him up for good,” he told his mother.

Creating a long-running series featuring a much-loved character can be both a blessing and a curse. As time passes in the real world, the writer has to decide how to deal with a fictional timeline. Is it best to age a hero in real time – Ruth Rendell had Inspector Wexford still solving crimes in his retirement – or to let the world move on but keep your hero young, as Patricia Cornwell does with Kay Scarpetta, who remains around 40 years old for ever ? And how does the character develop as social mores change? Writing about police can be a challenge now. As Attica Locke says of her Texas ranger in her Highway 59 series, “writing a cop is something I thought I’d never do”.

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, John Connolly argues that “a mistrust of the police – a mistrust of the establishment, really – runs through the private eye genre”. “The police represent the law, but the private eye represents the possibility of justice, particularly for those for whom the forces of law and order refuse to stand up: women, minorities, immigrants. For me, a conception of social justice lies at the very heart of the genre.” Sara Paretsky sees crime fiction as the form “where law, justice and society come together in a natural way – that is, you can write about them without being polemical or didactic”. Child says his plots have always “included corrupt, negligent and deficient police departments and federal agencies”. Twenty years ago, though, “people would write to me and say, c’mon, that wouldn’t happen. Now no one says that. Clearly reality is slowly dawning.”

Then there’s the question of how, or indeed whether, to draw a series to a close. Christie kills off Poirot in Curtain, and Conan Doyle did his best to wave farewell to Holmes, sending him plummeting to his doom down the Reichenbach Falls.Readers were distraught; the author quietly rejoiced – “I hold that it was not murder, but justifiable homicide in self-defence, since, if I had not killed him, he would certainly have killed me” – but by 1903, he’d resurrected him, with fans discovering in a new short story that Holmes hadn’t really died – he’d merely been fooling his enemies.

To avoid any such reversals, the late Andrea Camilleri wrote the final novel in his Inspector Montalbano series 14 years ago, giving it to his publisher for safekeeping: “When I get fed up with him or am not able to write any more, I’ll tell the publisher: publish that book. Sherlock Holmes was recovered … but it will not be possible to recover Montalbano. In that last book, he’s really finished.” But what of today’s detectives? How do their authors coexist with their characters over years – sometimes decades – and what lies ahead?

Lee Child on Jack Reacher

24 books

If you study English literature you’re taught the character must change and go on a journey. I want very much the opposite. As a reader I love series for the familiarity, so I’ve put effort into stopping Reacher from changing.

The best thing to do is not to get too close to the character. I need to like him less than you’re going to like him. That’s what keeps him alive and honest and authentic. There are many series where the author clearly falls in love with the character and starts to be too protective. I’ve always been very hardhearted. I don’t like Reacher that much; I’m in total control of him. I’m the only person in the world he’s scared of.

Initially I had the idea that in the last book, he would die in a blaze of glory or noble self-sacrifice. I even had a title, Die Lonely. But it dawned on me that would be gratuitously cruel to the reader who had supported him for so long.

So I thought maybe we could have a metaphorical version, where he’s heading for the bus depot to leave town but stops and thinks, “maybe I’ll stay here and adopt a dog”. But I moved through that and thought: “Let’s let Andrew keep it going.” He really is me 15 years ago, still full of energy, still full of ideas, and so I think this is the perfect solution. I will always continue to tell these stories in my head.

Attica Locke on Darren Mathews

two books

I never had any intention of doing a series. And then I went to work in television and it was fun to hang out with characters for a long period of time. Darren was the last piece of the puzzle. I was infinitely more interested in location and in telling a very Texas story, in particular a story about Highway 59, which is a route through the eastern part of the state. All of my family are from little towns along this highway, and my idea was that every book would be about a different town and a different crime, but I didn’t have anyone at the centre of it, and I had to figure out who that would be.

So I’m thinking of a character who could be involved in crimes across the state. Who could that be? Is it a lawyer, is it a PI, who has that kind of range? And I went: “Oh! A Texas ranger – that’s literally what they do, range.” Once I knew I wanted to write about a ranger I had to educate myself, and get comfortable with the idea. I’m married to a criminal defence attorney, I’m a black American, my whole thing was that I don’t see the world through a cop’s eyes, what am I going to do? Then I read a book called Ghettoside by Jill Leovy, which is about police failing to catch and prosecute people who commit crimes against black life. In it there’s a black cop who works with the police in south LA, and his approach is: “I wear the badge in order to protect the black folk who live in this neighbourhood.” And when I read that, it’s like my mind could shift, and I could understand writing a black cop. I also gave him all the same ambivalence I have about law enforcement.

I have a sense this series is four books. It blows my mind to think of writing these for ever, it terrifies me. I know what Darren will be up against in book four, but I don’t know how the whole thing ends.

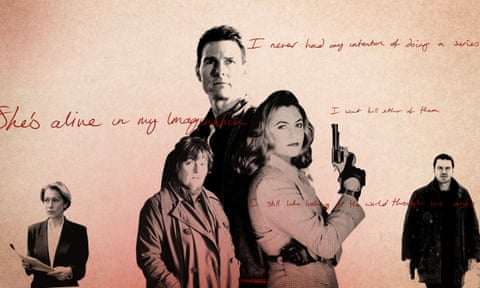

Val McDermid on Tony Hill and Carol Jordan

11 books

I had the idea for a psychological profiler. I thought if I made the liaison in the police a female officer that would give it added tension. At the time there really weren’t many women in senior positions. I didn’t know at that point it would be a series but as I progressed through the novel it seemed to me that not only were Tony Hill and Carol Jordan interesting characters, the jobs they did meant I could draw in other topics.

If I’d thought it was going to be a long-running series I would probably have set it in a real city. Writing in a fictional city gives you lots of opportunities – when you want a premier league football team you just stick it down in the middle – but you never have that same sense of solidity. But I made the decision because I knew that this novel was going to be critical of the police and I really didn’t want to get done for speeding.

I feel an affection for Tony and Carol, a sympathy for what they’ve been through. Who knows how old they are? They’ve probably aged about one year for every book, rather than in real time. It’s fiction and I can do what I want. I guess they’re about mid-40s.

The one thing I’ve promised readers is that I won’t kill either of them. But I’ve never had an overall arc. Can you imagine being Sue Grafton and sitting down and writing A Is for Alibi and thinking: “Well only 25 to go?”

John Connolly on Charlie Parker

18 books

The spark for Charlie Parker was an image of a man going to visit the grave of his wife and child, flowers in the back of the car. For me the big thing was letting the characters grow older. You can take the Patricia Cornwell route, which is to keep your characters a certain age all the way through but the series can’t really develop if you do that because you’re just going to keep repeating certain tropes, the character is set in aspic. The other option is to do what somebody like James Lee Burke has done with Robicheaux, who ages with the writer effectively. Robicheaux is into his early 70s, so the books become meditations on mortality.

As the characters age, the nuances, the textures of the books change. There’s a misapprehension about mystery fiction, which is that people read for plot. They don’t – the plots really don’t change much. There’s a murder. There’s an investigation. There’s a solution, however partial. Plot is what characters do and language is the expression of that, and so for a mystery series what keeps people coming back is the pleasure of spending time with those characters.

If my doctor said don’t go booking any holidays after November, I know how I would choose to end the series. For the moment, though, I still like looking at the world through his eyes.

Ann Cleeves on Vera

nine books

I had this idea for three women who were doing environmental surveys in Northumberland. I killed one of them off, and about a third of the way through, because I don’t plot at all, I got really stuck. That’s when Vera appeared like magic, through a door in a funeral home, fully formed with her name, looking more like a bag lady than a detective. I hadn’t planned her. But of course characters don’t come out of nowhere, so I think she came from the spinsters that I knew in the small town where I grew up – very strong, very competent, didn’t care what they looked like.

Once she’d appeared I wanted to write more about her, and about the places in the north of England where I lived: the vast empty inland hills, and Hadrian’s Wall, the beaches and castles and post-industrial communities. Vera’s definitely not ageing in real time. In my head she’s in her mid-to-late 50s and she was that 21 years ago. The world around her goes forward in real time.

With my Shetland Island series, I knew that I was only going to do eight books, because Shetland doesn’t have that variety of landscape or community and there are only 23,000 people who live on the islands. You can’t kill them all. So I knew that towards the end of books seven and eight, I had to be thinking about how it was going to end.

I would struggle to write just one series with one character. I can come to the end of a Vera book now and think I’m going to find out a little more about Matthew Venn, my new character. He comes from north Devon, which is where I grew up. He is gay. He’s got a husband, and he comes back to Devon because of his husband’s job. It was a bit daunting starting a new series, but I’m just starting the second Matthew book. It’s great to write about a happy marriage. I’ve never done that before.

Amer Anwar on Zaq Khan

two books

Ex-con Zaq Khan and his best friend Jags are drawn from me and my friends. I grew up in Ealing and hung out a lot in Southall. It was a really colourful area, and there were two authors who made me think I wanted to set a story there. The first was Elmore Leonard; his heroes aren’t always policemen, sometimes they’re just ordinary people, sometimes they’re small-time criminals, and I thought “Wow, you don’t have to write from the detective’s perspective if you’re writing a crime novel.” And then I read Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins books, set in the black community in LA in the 1940s, and I saw you could tell those stories through a character of colour. It was the sort of book I was hoping someone would write, but no one had done it.

Even though Zaq is done for a violent crime, he’s the main character and I wanted people to root for him and empathise with him. It was about allowing the reader to see that he’s not a bad person and he has a moral code; he wants to do the right thing. I wrote Brothers in Blood as a standalone. It got rejected by about 30 publishers, basically down to it being too Asian, so I self-published it, and then it got picked up by Dialogue.

The second book, Stone Cold Trouble, is out in September. It’s set a few months after the first. When I’m writing the next book I’ll have to be referencing the lockdown and Covid-19. I may do that but in a very light way.

Ian Rankin on John Rebus

22 books

I had an idea of writing about contemporary Edinburgh and trying to show its darker side, and I thought a cop was a good way to do that. By book number four, I thought: Oh, this guy is sticking around. Mainly because I enjoy spending time with him – he’s a complex character. And because a detective is a very good way of looking at society. I wanted to take on politics and issues to do with people feeling dispossessed or disenfranchised. Rebus would allow me to look at the world, from the people who’ve got everything down to the people who’ve got nothing.

I made the decision early on that he would age more or less in real time. And there are problems with that, as I’ve discovered. He had to retire. He retired twice, in fact. He retired at the end of Exit Music because he had hit the mandatory retirement age for police detectives in Scotland. I found a way to keep him in the force working as a civilian for a while. Then even that had to come to an end.

But I keep finding things for him to do. I’m writing one at the moment. He’s got health issues now but he’s still getting into trouble and mysteries are still there to be solved. Maybe this is the final book. I have no idea until I get to the end.

Sara Paretsky on VI Warshawski

20 books

It was something that I had wanted to do ever since I first read Raymond Chandler. In six of his seven novels, it’s a woman who’s sexually active who turns out to be the main villain. And I just was tired of this femme fatale idea in a lot of crime fiction, that women who use their bodies to try to get good boys to do bad things inevitably come to a terrible end.

I was working in the corporate world in the financial services industry, for a real pill of a guy, and I was looking out at the dead trees in Grant Park and the balloon over my head was saying something unprintable while my lips were saying something sweetly soothing to the male vanity. And at that moment, really, quite truly, VI came to me. I thought, she is someone who says what’s in the balloon over her head. She is not interested in making nice. She’s facing the challenges that women did face in the 1980s, being pioneers in occupations that had been shut off to women over the centuries.

When I started, I wanted her to age in real time. As time passed, I’ve stopped her age around 50 because I just don’t want VI to be helpless. As the world becomes an ever more shocking place, it’s important to me to have someone who’s really vibrant and not going to be mowed down. Physically she has to be very tough as well.

People in the industry talk about the character being your “brand”. Well, thank you, she is not Pampers or a tampon, she is a person alive in my imagination, not a commodity to be bought and sold by other people.

Abir Mukherjee on Sam Wyndham and Surendranath Banerjee

four books

I always knew I was going to write a series. I wanted to look at the period of British rule in India between 1919 and independence and in my head, rather naively, I thought, right, I’m going to do one a year: 1919 all the way to 1947. Four and a half books in, am I going to? I doubt it.

Sam Wyndham and Surendranath Banerjee came to me as a package. That’s partly because they’re really just different aspects of my own personality. Sam is my jaded Scottish side; even though he’s English he has a very Glaswegian, gallows humour. Suren is my Indian side, my more questioning side. When you grow up between different cultures, you have this inner dialogue that just goes on constantly.

I’ve always known that there will be a falling out between the two. I’d like to see Suren as the first non-white chief of police in Calcutta, in independent India, but there’s a long way to go before that. The story I really want to tell is 1943, the story of the Bengal famine. I don’t feel confident enough to write it yet. It’s such an emotive subject, I think you need to have a readership with you, to tackle issues like that.

When I started out, Sam and Suren were essentially tools to tell the story of colonial India but they’ve become so much more to me. I never thought I would fall in love with them the way I have. I’m not sure I could kill them off, it would feel a bit like amputating part of myself. I’d like to see them have a long, happy retirement one day.

Lynda La Plante on Jane Tennison

four books

Nobody expected that the television series Prime Suspect would become such a monster hit. I went to the Met and said: “Do you have any high-ranking female plain clothes detectives?” I was told “Yes, we have three.” One of them, a DCI, was called Jackie Malton, and I followed her for months. She was determined I would get it right, and she opened up avenues which, without her, I never could have got to.

Now I’m writing a new series about DC Jack Warr. You don’t want to create something that everyone says: “Seen it, heard it, boring.” I began to notice how often in fiction we were seeing troubled heads of departments: a DI with a marriage problem, a drink problem, drugs problems, his wife was leaving him, his daughter was a heroin addict. So I wanted to create somebody who was a perfectly happy, lovely guy. No problems whatsoever, a great relationship, adores his parents. I wanted to write a character who you saw going through the process of learning to be a detective.

Michael Connelly on Harry Bosch

22 books

I was a journalist covering real detectives, and at night trying to write fiction about detectives. In 1988, I spent a week with the head of the homicide squad in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The next thing I wrote ended up being the first Harry Bosch book. I loved reading series, so writing one was my goal in life. I really set the character up so that I could write more about him. I gave him an unsolved mystery in his life, his mother’s murder.

I’d clearly said in that first book that he was 42 years old, and my plan was to write in real time so he’d really age. If I’d had any inkling that I’d be writing about this guy for 25 years or more, I would have made him younger. But I’ve stuck with that and now teamed him up with a younger detective, I think that’s one way of keeping it going. He’s not going out to pasture, but it’s been five years or more since he’s actually been a real cop, because it’s not believable that some 70-year-old guy would still have a badge and a gun and work for the LAPD.

Mark Billingham on Tom Thorne

16 books

Really I wanted the first Tom Thorne book, Sleepyhead, to be about the victim of a particular crime, so I just sort of dumped this copper on the page without thinking too much more about it. I never dreamed I’d be writing about him 20 years later.

Maybe I should have made him a little bit younger but I thought he’d be easier to write if he was the same age as me. I’ve slowed him down a bit. Also I’ve stopped specifying when a book is set because I realised quite early on that you can get into trouble. If you’re writing about a real city – the books are set very much in a real London – you can be quickly overtaken by events.

The book I have coming out this year is a prequel, so I’ve been able to go back and set it in the mid-1990s, with Thorne as a much younger man. That’s been hugely liberating, not just because of the fact that I’m writing about a world that isn’t dominated by CCTV and the internet.

It will end when I’m not interested in writing about it. I don’t see him running an antiques shop in the Cotswolds but I would fight shy of killing him off. He’s someone I’m incredibly close to and I don’t want to think about his end more than I do my own. If he was going to go, he would be listening to George Jones or Hank Williams while watching Spurs.

Jo Nesbø on Harry Hole

12 books

I was on my way to Australia back in 1997, and I had promised an editor I’d write something. She wanted me to write about my band at the time but I had five weeks in Australia and thought I would write a short crime novel so I needed a protagonist for that. I sat on the plane to Sydney and came up with Harry. I didn’t put much analysis into it. It was more instinct – I knew I wanted a character that was partly a traditional, hard-boiled detective, combined with characters I knew from my own life. I had no idea he would be with me for so long – I thought it was a one-off.

It’s easier the more I write about him – I get to know him and I know my readers know him. There will always be emotional and psychological contradictions which make him interesting to me. As you get older you’re more interested in your old friends than getting new friends, and it’s a bit the same with Harry.

I have a clear idea for the storyline of his life. I won’t tell you what it is, though.