The nineteenth century saw amazing advances in science and technology. Many inventions – such as railways, the telegraph, the telephone and the light bulb – were so successful that they changed the way we live. At the same time hundreds of lesser known or amateur inventors were hard at work on their ideas, many of which have long since been forgotten about or never saw the light of day. Those inventions are the subject of my new book called Inventions that didn’t change the world, published on 6 October by Thames & Hudson, which takes a humorous look at some of the more eccentric inventions registered for copyright.

The nineteenth century saw amazing advances in science and technology. Many inventions – such as railways, the telegraph, the telephone and the light bulb – were so successful that they changed the way we live. At the same time hundreds of lesser known or amateur inventors were hard at work on their ideas, many of which have long since been forgotten about or never saw the light of day. Those inventions are the subject of my new book called Inventions that didn’t change the world, published on 6 October by Thames & Hudson, which takes a humorous look at some of the more eccentric inventions registered for copyright.

Among the shelves at The National Archives are huge leather-bound tomes containing fascinating drawings of inventions registered under the 1843 Utility Designs Act. The Act gave copyright protection to the new elements of ‘useful’ designs, as opposed to purely ‘ornamental’ designs such as ceramics, wallpapers, and textiles, which had been covered by copyright since 1839. The Act came to be seen as a quicker and cheaper alternative to the notoriously expensive and convoluted patent system, which involved visits to as many as 10 different offices, with fees payable at each. A design could be registered at a cost of £10 for three years’ copyright protection, whereas a patent could cost as much as £400 for 14 years’ protection.

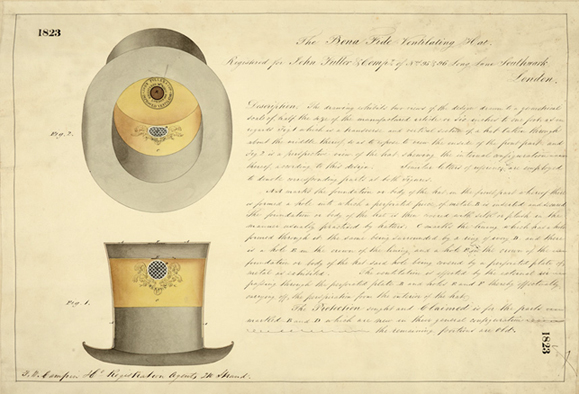

Smaller-scale inventors seized the opportunity to register their designs. From ventilating top hats to artificial leeches, a flying machine for the Arctic to an ‘anti-garotting cravat’, these drawings give us a unique insight into the social history of the period. If they wanted to copyright their work, the inventor had to take two identical drawings of the design to the Designs Registry at Somerset House in London, as well as providing the title of the design, explanatory text, and a description of which parts of the design were new and original. What was called the ‘object of utility’, or purpose of the design, was also described. Both copies of the drawing would be stamped with a registered design number. One would be returned to the copyright holder, or ‘proprietor’, and the other would be pasted into a huge volume of designs and retained by the Registry, part of the Board of Trade. As government records, these eventually came to The National Archives for safe-keeping.

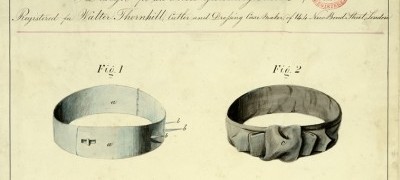

A design for an anti-garotting cravat, registered by Walter Thornhill, cutler and dressing case maker, London, December 1862. BT 45/23/4530

Many designs which seem completely bizarre at first make sense within their historical context. Even so you can’t help but wonder how many lives were saved by the ‘anti-garotting cravat’. The design was registered at a time when there was a major panic about incidents of garrotting. At the time this meant a form of mugging where the victim was held around the neck and robbed. Not surprisingly, this sometimes proved fatal. The scare coincided with the end of the system of transporting criminals to the colonies. Large numbers returned home with a form of conditional pardon called a ‘ticket of leave’. There was widespread fear of ‘ticket-of-leave men’, as they became known, who were believed to be responsible for an increase in violent crime. In 1862, the year this design was registered, an MP called Hugh Pilkington was the victim of a garrotting robbery. A celebrity victim increased the sense of panic and triggered widespread discussion about methods of self-protection. Sadly, no record has so far come to light showing that any robberies were foiled by this invention, consisting of large spikes at the front of the collar, cunningly concealed by a cloth cravat.

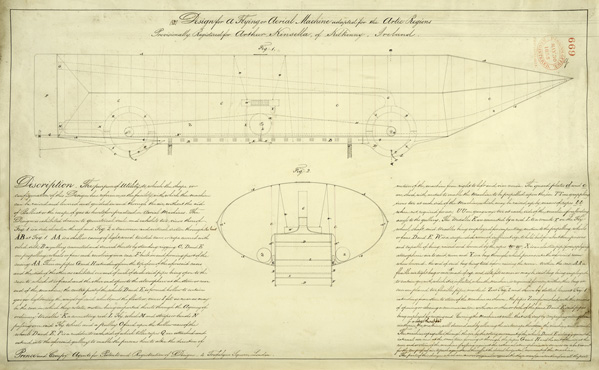

A design for a flying or aerial machine adapted for the Arctic regions, registered by Arthur Kinsella, Kilkenny, Ireland, May 1855. BT 47/4/669

The ‘flying aerial machine adapted for the Arctic regions’ was designed at a time when the newspapers were full of stories about Arctic exploration and the exploits of individual explorers. In particular there was a race to find a trade route through the Northwest Passage – and to find the expedition of Sir John Franklin, which disappeared while searching for the route in 1845. Rescue missions continued until 1859. The date of registration of this design, in 1855, suggests that the inventor thought he had found a solution to navigating Arctic terrain, although the first really successful airship wasn’t built until over 40 years later. The text that accompanies the design tells us that treadles turn the wheels, which would contain gas to make them lighter. A suspended room holds beds for three people, supplied with air by an ‘elastic pipe’, and metal plates underneath the aerial machine would allow the aerial machine to be propelled along the ice.

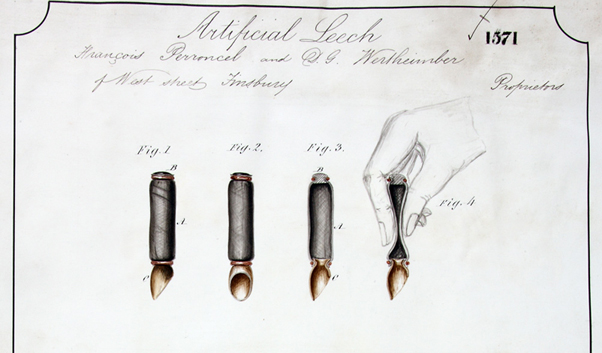

Artificial leech, registered by D G Wertheimber and Francois Perroncel, London, September 1848. BT 45/8/1571

The nineteenth century was a period of great medical advances, but for much of the century there was an overlap between traditional practices that we would now regard as totally unscientific and new discoveries based on solid scientific evidence. One form of medicine that had been practised for centuries, and remained popular in the nineteenth century, was the use of leeches for blood-letting. An excess of blood was thought to be responsible for many conditions, and leeches were used to treat everything from headaches to prostate problems. Contemporary accounts refer to ‘a mania for leeches’, and eventually their numbers dwindled enormously. It is around this time that we see several registrations for ‘artificial’ or ‘mechanical’ leeches, which used various methods to drain blood out of the body. They also got around any squeamishness: one inventor promoted his product on the basis that it helped patients ‘overcome their repugnance to contact with the cold and slimy reptile’.

Some of the designs shed light on problems people used to live with that we’ve long since forgotten about. For about 100 years middle class British men wore top hats, and hot heads were obviously quite a problem, as there are several designs for top-hats with built-in ventilation systems. Most men used hair oil, and along with perspiration, quite an unpleasant atmosphere could build up within the hat. This particular one, ‘the bona fide ventilating hat’, has a kind of grille to let air in and ‘carry off perspiration from the interior’, as the description tells us.

Most of the inventions illustrated in this book will never have been seen by anyone but a very few determined researchers. Not everyone can get to The National Archives to see the original documents for themselves, and the documents are in any case extremely heavy and difficult to handle. Inventions that didn’t change the world is a window into the curious world of lesser known Victorian inventions.

Fascinating subject and an inventive way of using your patents’ archives. Thanks!

Hello Julie,

Brian Moyse here,formerly from Essex but now in Texas.Thank you so much for your interesting book & for the ‘on-line’ video.Most enlightening & entertaining too,makes me envious that I do live close enough to frequent TNA myself to look for that ‘missing link’.

Especially so since I am looking for information about Rd 787232 which as far as I can tell has not yet been digitized.

Thanks & regards Brian.

An excellent and at times amusing article giving us a picture of the imagination of the inventers. One can only wonder what inventions followed