Two new international studies have shed further light on some of the harmful side effects associated with antibiotics – including damage to the immune system, and memory problems caused by a lack of growth in new brain cells.

The findings serve as a reminder that while antibiotics can be powerful allies for the human body in the fight against disease, they can also do more harm than good if used in the wrong situations (one of many reasons you should always follow the advice of your doctor).

Both studies found that the way antibiotics kill off microbes in the gut can cause health issues, due to the way the delicate chemical mixes in our bodies can be thrown out of balance by the medication.

The first study, led by researchers from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre in New York, involved 857 patients receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplants – a treatment typically used to tackle blood and bone marrow cancers. Antibiotics are usually given in these cases to prevent or treat infections linked to the transplants, but the researchers found that patient health varied depending on the types of antibiotics used.

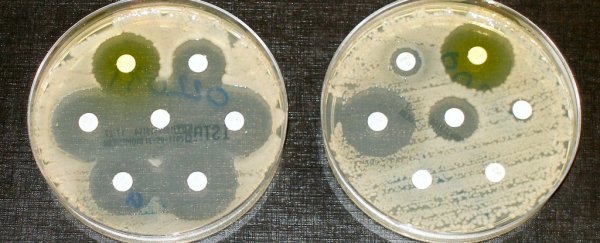

They tested 12 of the most common types of antibiotics, finding that two combinations in particular – piperacillin and tazobactam, and imipenem and cilastatin – led to a higher risk of a life-threatening inflammatory condition called graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

The hypothesis is that the 'mass exodus' these particular antibiotics caused in the patients' gut microbiomes harmed the body's immune system in some way. Similar results were observed when the researchers tried the same tests on mice.

The second study, led by a team from the Max-Delbrueck-Centre for Molecular Medicine in Germany, investigated the effects of broad-spectrum antibiotics – those that kill off many different types of microbes – on mice. They noticed a slowdown in brain cell development in the hippocampus, which is the part of the brain responsible for memory and controlling the nervous system.

These mice performed poorly on memory tests, and were also found to have fewer monocytes (white blood cells that fight off viruses) in their bodies. When the course of antibiotics was stopped, the mouse brains were able to rebound to their former state, according to the researchers.

Scientists involved in both studies have emphasised that there's more work to be done, and further tests to be run before we understand exactly what this means for the way we use these antibiotics in the future. For the time being, though, it's a good reminder that these drugs should always be carefully used – and not overused in any circumstances.

The first study is published in Science Translational Medicine, and the second appears in Cell Reports.