The feet were all wrong. To be precise, they were missing altogether. Just bone-colored stubs, but that in itself was not reason for suspicion. It was the way the stubs ended. Not torn, not broken, but cleanly cut, as if by a modern machine. Like a band saw.

It was the summer of 2012, and Prince Ravivaddhana Monipong Sisowath, known to his friends as Ravi, was staring at the cover of the Sotheby’s catalogue.

“My first reaction was, ‘once again, Sotheby’s,’” he recalls, followed by “this will be a hard recovery to make, because it is basically a problem of money and politics.” The footless statue was the star of the sale, estimated at around $2 million, yet it was obviously stolen, looted from a temple in his native Cambodia, the country from which his family—the royal family—had been exiled since 1970, and in which he had first set foot in 2000, aged 29.

“I wondered, how can you give a price to something so precious that to me it cannot have a price? I was totally shocked.” He picked up the phone and made some calls. Within minutes he knew exactly which temple the life-size statue had been looted from. He knew, because its feet were still there.

The statue in question is called the Duryodhana, and depicts the protagonist of a Sanskrit Hindu epic (thought to have been penned in the 9th century BC), the “Mahabharata.” Duryodhana was the eldest of one hundred sons of a blind king, but was muscled out of place as rightful heir when his cousins, the Pandava brothers, led by Bhima, claimed the throne instead. The life-sized statue was sculpted around the 10th century, during the height of the Khmer empire. It had been consigned to Sotheby’s in 2011 by a Belgian collector, but experts suspect that it had been looted sometime in the 1970s.

Prince Ravi shook his head and sighed. This was but the most recent, and highest-profile example of a trend that has lasted decades, with its origins in the systematic looting of Cambodian religious sites by the Khmer Rouge, the Communist regime that seized power on 18 March 1970 and prompted the exile of the royal family, a year before Ravi was born. It is both alarming, and offers hope, that more statues, looted at the same time and from the same temple complex, keep coming onto the market. But they also keep getting identified and returned. Within one week in March of 2016, three statues were triumphantly returned to Cambodia and installed at the National Museum in Phnom Penh: a pair of 10th century Brahma heads and a Rama statue.

Just this week it was reported that the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, backed by the United Nations, investigating for over ten years and costing some $300 million, has convicted just three people linked to the deaths of an estimated 1.7 million Cambodians between 1975-1979. While the world wonders whether this tribunal can be considered a success, much less cost-effective, and whether real justice is being done, it is easy to forget that there were non-human victims of the Khmer Rouge, and that they continue to be used for illicit ends. Illegal trade in Cambodian cultural heritage, the looting and sale of priceless ancient statuary, continues to this day and is a lasting reminder that the casualties of the regime extended beyond human life, but cut into the roots of the culture itself.

Ravi recalls the first object that drew his attention to the fruits of rampant looting in his homeland.

“When I first arrived in Rome, in 1997, there is a shop next to Palazzo Farnese. I went into it because I thought I might be able to afford to buy what I thought was a copy of a Cambodian statue in the window. Then the man named a price which was absolutely incredible. I said, ‘Do you mean that this piece is authentic?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ I said, ‘Then you are a thief.’” Throughout the Cambodian Civil War (1970-1998) trafficking in looted antiquities, largely taken from temple complexes, was commonplace.

There is no estimate as to the number of works stolen, damaged, or destroyed, but visitors today, without venturing off the beaten path, can see hundreds of empty plinths and niches that once housed artworks. It would be a rare and unusual thing to find an authentic Cambodian temple statue on the market that was not stolen.

Dr. Simon MacKenzie, a criminologist who studies looting in Cambodia as part of the Trafficking Culture research group, which was based at the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research at University of Glasgow, explains: “Many temple sites we visited were empty shells—still magnificent, of course, but hollowed out by the theft of the statuary. There is a great sadness which comes with visiting these sites, which while still great have been so severely diminished. Everywhere you turn there are plinths with just the feet of a former statue remaining, or statues without heads.”

It was back in the 1970s that the Duryodhana was stolen, cut off at the feet to facilitate transport, and smuggled into Thailand and then abroad, for sale in Europe. Most of the looting during the time of the Khmer Rouge was organized by that regime, and therefore funded their activities, which ranged from terrorism to genocide. Unfortunately, remnants of the trafficking networks of the Khmer Rouge era remain in place to this day.

Prince Ravi was not the only one to have noted the cover of the Sotheby’s catalogue. The Cambodian government formally requested the removal of the statue from the sale on the morning it was to be auctioned. Sotheby’s removed the statue from the sale, but refused to hand it over to the Cambodian government, considering it to be the property of the woman who consigned it. Like all auction houses, Sotheby’s is a middle man. It sells for a commission, but does not buy works directly, so it is not unreasonable that it should refuse to hand over an object on consignment. However insult was added to injury when a Sotheby’s representative suggested that the Cambodian government buy the looted statue from the seller.

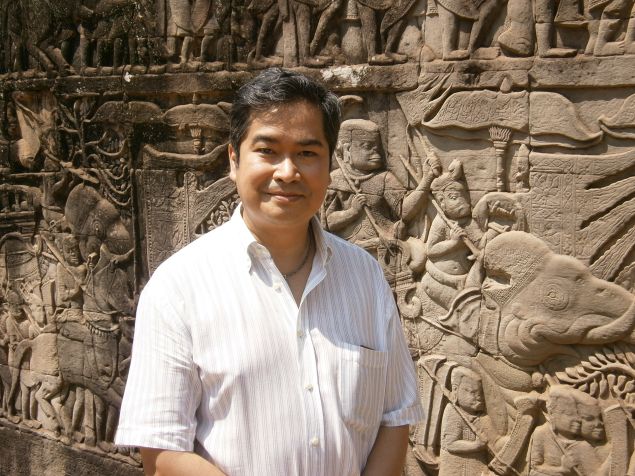

Ravi, the great-grandson of King Sisowath Monivong and one of a bevy of Cambodian princes and princesses, wears the soft face of a beautiful youth, a lively smile, and the silky movements of a trained dancer. He is the most outspoken and dedicated member of the royal family when it comes to the looting of Cambodian temples, like the Prasat Chen temple at Koh Ker, the source of the Duryodhana. While he is more figurehead than foot soldier in the prevention and recovery of looted antiquities, he does what he can to assist the few willing to go into the field, who encounter organized criminals and even terrorists. People like Simon MacKenzie.

Dr MacKenzie’s Trafficking Culture team consisted of five researchers and five doctoral students (it was active from 2012-2016). He and one of his colleagues, Tess Davis, travelled to Cambodia to visit looted sites and do what they could to track down those responsible. What they found was frightening in scale, organization, and physical menace.

“We have established a picture of a funneling network that moves statues from various temples in Cambodia and passed them into a small networks of channels that moved them by oxcart, truck and even elephant out of the country and into Thailand,” wrote MacKenzie in a recent article in the British Journal of Criminology. MacKenzie was able to identify specific criminal networks, routes taken by looters, and even individuals responsible for the looting. “Organized criminals with no military affiliations were active in the looting of Cambodia,” he writes.

The illicit trade in antiquities went hand-in-hand with the drug and arms trades, and murders were committed to solidify claims on looting sites and smuggled routes. It has been alleged that the looting of the Koh Ker site may have been done under through the personal intervention of Ta Mok, one of the most notorious of the Khmer Rouge masterminds of genocide, who was called The Butcher. But while there was a historical component to this research, the worrisome fact is that it is still going on. While interviewing locals during his research trip, a looter in Thailand offered Dr. MacKenzie any Cambodian antiquity he might like from a temple, if he would bring a photograph of it.

In 2013, a successful lawsuit was filed by the U.S. District Attorney’s Office, for the return to Cambodia of the Duryodhana. Also in 2013, the Metropolitan Museum of Art voluntarily returned a pair of comparable statues, perhaps taken from the same temple complex, referred to as the Kneeling Attendants, but who actually represent two of the Pandava brothers, the rival claimants to the throne in the epic “Mahabharata.”

In May 2014, yet another statue from the Koh Ker complex, the Bhima, was returned from the Norton Simon Museum in California, where it had been a star of the collection since it was bought from a New York dealer in 1976. It had been looted from the same temple, Prasat Chen, in the Koh Ker complex, as had the Duryodhana. Bhima, like the Kneeling Attendants, were all representations of Pandava brothers. Bhima’s feet, still on site at Prasat Chen, were identified in 2006 by a French archaeologist, Eric Bourdonneau, who produced a digital image that matched the feet in Cambodia to the rest of the statue in the United States.

By April 2012, a month after the Duryodhana was featured on the Sotheby’s catalogue, archaeologists in Cambodia further excavated Prasat Chen and found nine pedestals, all of which had once contained statues from this same group—four of which would shortly be restored.

The returned statues were displayed together in May 2014 in a special gallery Cambodia, unveiled in an elaborate ceremony, as Ravi explained at the recent ARCA Conference on the Study of Art Crime, at which he spoke. More recently-returned statues now join them. There is a likelihood that more will follow. That’s a good thing, since it shows that looted antiquities will not continue on the market, and will be returned to their rightful home. But it is also likely that these majestic works are just the tip of the iceberg of what is still out there.

As for the new returns, including one that had been acquired by the Denver Museum of Art in the US, Prince Ravi is encouraged, but the quest continues. “The recent return of Rama from Denver is only one further step of the process. To tell you the truth, we are now hunting for his head.”

This is the latest in Observer Arts’ series Secrets and Symbols, by author and art historian Noah Charney.