A Brief History of Unisex Fashion

Gender-neutral clothing is back in vogue, but the craze in many ways has mirrored broader social changes throughout the 20th century.

In March, the London department store Selfridges gave itself a radical makeover, transforming three floors of its Oxford Street emporium into gender-neutral shopping areas. Androgynous mannequins wore unisex garments by designers such as Haider Ackermann, Ann Demeulemeester, and Gareth Pugh, and the store’s website got a similarly sexless redesign, displaying the same products on both male and female models. Dubbed “Agender,” the temporary pop-up shopping experience—or experiment—ultimately proved to be more successful as a marketing tool than a retail revolution; as some fashion journalists have pointed out, today’s clothes “are much the same for each sex anyhow.”

But that wasn’t always the case. As Freud put it: “When you meet a human being, the first distinction you make is ‘male or female?’ and you are accustomed to make the distinction with unhesitating certainty.” Had Freud lived through the 20th century instead of the 19th, he might have had good cause for hesitation. In an era when gender norms—and many other norms—were being questioned and dismantled, unisex clothing was the uniform of choice for soldiers in the culture wars.

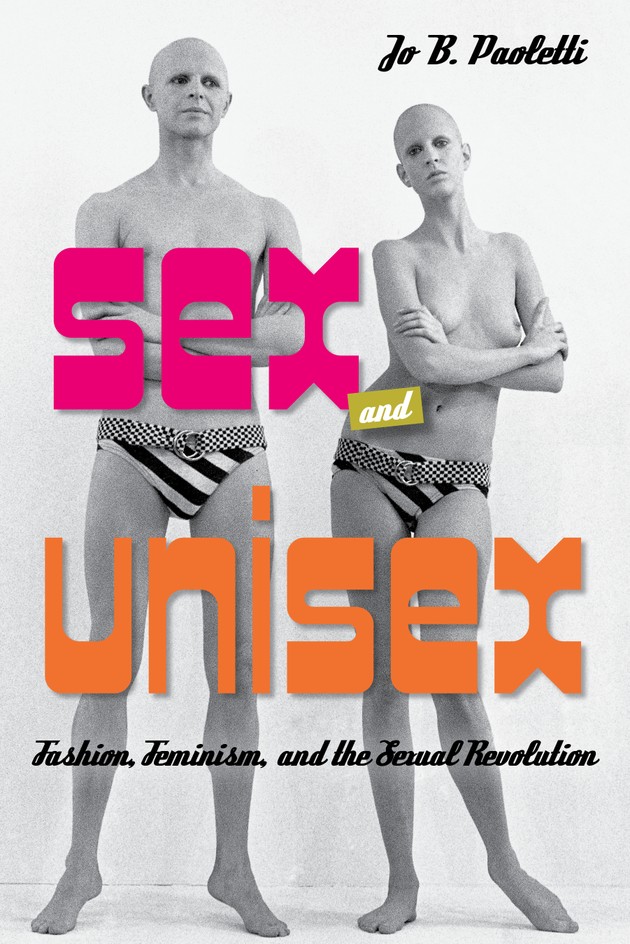

In her new book Sex and Unisex: Fashion, Feminism, and the Sexual Revolution, the University of Maryland professor Jo Paoletti revisits the unisex trend, a pillar of second-wave feminism whose influence still resonates today. As Paoletti tells it, unisex clothing was a baby-boomer corrective to the rigid gender stereotyping of the 1950s, itself a reaction to the perplexing new roles imposed on men and women alike by World War II. The term “gender” began to be used to describe the social and cultural aspects of biological sex in the 1950s—a tacit acknowledgement that one’s sex and one’s gender might not match up neatly. The unisex clothing of the 1960s and 70s aspired “to blur or cross gender lines”; ultimately, however, it delivered “uniformity with a masculine tilt,” and fashion’s brief flirtation with gender neutrality led to a “stylistic whiplash” of more obviously gendered clothing for women and children beginning in the 1980s.

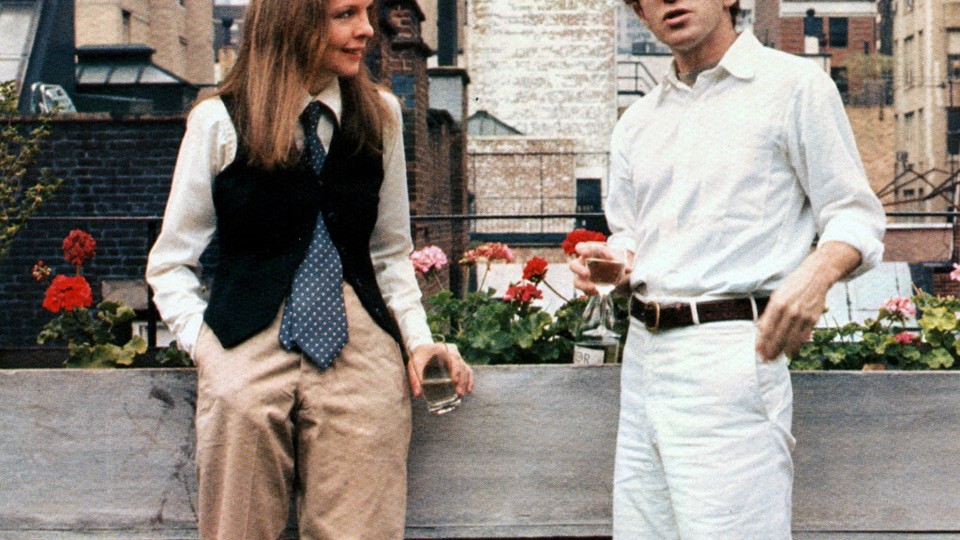

As far as the American fashion industry was concerned, the unisex movement came and largely went in one year: 1968. The trend began on the Paris runways, where designers like Pierre Cardin, Andre Courreges, and Paco Rabanne conjured up an egalitarian “Space Age” of sleek, simple silhouettes, graphic patterns, and new, synthetic fabrics with no historical gender associations. As women burned their bras (symbolically if not literally), U.S. department stores created special sections for unisex fashions, though most of them had closed by 1969. But their impact could be felt for a decade afterwards in “his-n-hers” clothing, promoted in cutesy ads, catalog spreads, and sewing patterns. “The difference between avant-garde unisex and the later version,” Paoletti argues, “is the distinction between boundary-defying designs, often modeled by androgynous-looking models, and a less threatening variation, worn by attractive heterosexual couples.”

Children bore the brunt of the unisex craze: pants for girls, long hair for boys, and ponchos for everyone. “Baby boomers and Generation Xers tend to have very different memories of the unisex era,” Paoletti notes, and her book allows readers to admire the progressive intentions behind the trend while cringing at the result. Though parents feared that enforcing rigid gender stereotypes could be harmful to kids—fears stoked by emerging scientific evidence that gender roles were learned and malleable at a young age—the embarrassment of being mistaken for a member of the opposite sex left lasting psychological scars on many of their offspring. Young children had worn gender-neutral clothing (and played with gender-neutral toys) for decades before “unisex” became a buzzword, but the aggressively “non-gendered” child rearing of the 1970s took neutrality to a new level; children’s books and TV shows made a point of showing boys playing with dolls and women tinkering with cars. It was only in the 1980s that the self-actualizing lessons of the seminal children’s book (and celebrity-narrated LP) Free to Be … You and Me succumbed to the Princess Industrial Complex, a trend that is just now beginning to correct itself. (A 35th anniversary edition of Free to Be … You and Me was released in 2008.)

Although unisex clothing aimed to minimize gender differences, it usually had the opposite effect. As Paoletti writes, “part of the appeal of adult unisex fashion was the sexy contrast between the wearer and the clothes, which actually called attention to the male or female body.” Take the costumes fashion designer Rudi Gernreich—inventor of the monokini and the unisex thong—created for the 1975-77 television series Space: 1999. Gernreich envisioned 1999 as a gender-neutral utopia of jumpsuits, turtlenecks, and tunics. While technically unisex, these tight-fitting costumes made the wearer’s sex glaringly obvious, and they retained traditional gender markers such as bras, makeup, and jewelry for women.

The unisex movement may have made women’s clothes more masculine, but it never made them unfeminine; furthermore, “attempts to feminize men’s appearance turned out to be particularly short-lived,” Paoletti notes. (Even today, it’s mainly women who are buying unisex garments, not men.) While some men attempted to reclaim the flamboyance that had disappeared with the French Revolution, for many this so-called Peacock Revolution “raised the specter of decadence and homosexuality, a fear reinforced by the emergence of the gay liberation movement.” The irony, Paoletti points out, was that “at that time true homosexual men tended to be purposely invisible … To do otherwise was to risk one’s career or even being arrested.” The new popular and scientific interest in bisexuality was truly liberating for homosexual men, offering them a culturally acceptable alternative to the closet. It was liberating for fashion, as well; if everyone was a little bit of each sex, clothing did not have to proclaim one or the other as loudly.

Thus, the novelty of matchy-matchy “his-n-hers” outfits and everyone-in-jumpsuits-futurism quickly burned out in favor of the sexier androgyny (which Paoletti defines as clothes combining masculine and feminine elements, rather than avoiding gender markers altogether). In 1966, Yves Saint Laurent introduced le smoking, a tuxedo for women; over the next few years, he would reinterpret the mannish silhouette in gangster pinstripes and safari khaki. Halston made his name with the ubiquitous Ultrasuede shirtdress—a modern, feminine twist on a man’s shirt. As the current FIT Museum exhibition Yves Saint Laurent and Halston: Fashioning the Seventies illustrates, the designers weren't merely dressing women in menswear; they were dressing them as themselves, in classic pieces that reflected their own, subtly androgynous wardrobes. The exhibition catalogue argues that this “slick and functional style” associated with the international jet set was equally appealing to young, working women: not just trousers but pea coats, dress shirts, and blazers became female wardrobe staples.

Men, too, experimented with androgyny. Unusually, womenswear designers (including Pierre Cardin and Bill Blass) began to produce menswear lines; the mandarin-collared, button-front Nehru jacket (the Western name for the traditional Indian garment, after the first Prime Minister of India) was a Cardin signature. Along with tunics, vests, sport coats, and furs, the Nehru jacket offered men an alternative to the proverbial gray flannel suit; Nehru collars, ascots, turtlenecks, and scarves made neckties obsolete, at least temporarily. Today, women are still wearing pants to the office, but men have reverted to suits and ties.

Paoletti traces the end of the unisex era to the mid-1970s. In 1974, Diane von Furstenberg introduced her wrap dress, a garment that combined femininity and functionality. With its demure length, slit skirt, and deep V-neck, it was simultaneously modest and sexy; it could go from the office to the disco. The wrap dress wooed women away from pantsuits, landing von Furstenberg on the cover of Newsweek in 1976 under the headline “Rags & Riches.”

Since the 1990s, however, fashion has been blurring gender lines once again. A recent New York Magazine story traced modern androgyny to grunge: Women donned flannel lumberjack shirts and combat boots while Kurt Cobain posed in ballgowns and housedresses. (Cobain’s taste for off-the-cuff cross-dressing was evident in the most recent Saint Laurent and Gucci menswear shows.) At the same time, lookalike couples fashion (known as Keo-Peul-Look) first appeared in South Korea. This modern take on “his-n-hers” dressing caught on powerfully in a country where public displays of (physical) affection are frowned upon. Korean couples are androgynous by necessity, wearing skinny jeans, sneakers, sweaters, and hoodies; unisex garments are much more accessible and socially acceptable today than they were in the 1960s. But this careful coordination is not just an outward show; hardcore practitioners match down to their underwear. Thus, the ultimate relationship publicity has become the ultimate relationship intimacy, and unisex underwear is now a thing.

Indeed, unisex everything appears to be back with a vengeance; Rad Hourani even showed a unisex haute couture collection for Spring/Summer 2015. Personnel of New York divides its online offerings into Men, Women, and Everyone; labels like 69, Kowtow, and The Kooples encourage sex-swapping. Even the Space Age is new again; Christian Dior’s fall couture show included astronaut jumpsuits, while Gucci showed mod shifts and patent-leather boots. What are we to make of this gender confusion—or, perhaps, this adamant refusal to be gender-confused? “The fashions of the 1960s and 1970s articulated many questions about sex and gender but in the end provided no final answers,” Paoletti concludes. These questions went much deeper than Freud’s “male or female?” Clearly, we are still struggling to resolve them; just ask openly gay Louisiana teen Claudetteia Love, who nearly missed her senior prom because the school wouldn’t let her wear a tuxedo. Psychologically, there’s still a vast gap between a male garment adapted for a woman’s body and a male garment. Increasingly, however, men and women are wearing the same garments, bought from the same stores, in a retail landscape as rich, varied, and occasionally baffling as gender itself.