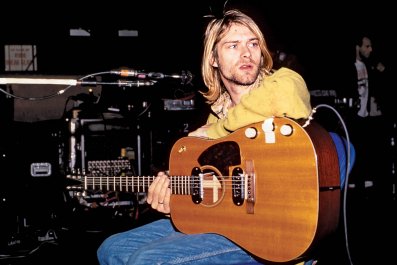

Danish telemarketing company Telehandelshuset has seen revenues and staff double over the past two years. Its agents are among the best in the business; they book meetings, make sales and do fundraising on behalf of clients. They are also blind, and part of a pioneering Danish trend: employing people with disabilities to help outperform competitors.

"Blind people have superior communication skills, and almost every company needs someone conducting telephone sales on their behalf," explains Connie Hasemann, Telehandelshuset's CEO.

Glad Design taps into the design skills of mentally disabled people with great success: it now supplies Tiger, the booming Danish homeware chain. At Bornholms Mosteri, which makes fruit juices and ciders now sold to Noma and other exclusive restaurants, more than half of the employees have a history of mental illness and take special pride in the success of their beverages. The Specialisterne and BOAS Specialister, two firms specialising in IT services, employ people with autism, benefitting from their exceptionally detail-oriented minds. Gamle Mursten ("Old Brick") employs people with mental illnesses to use a pioneering technology that allows old bricks to be cleaned of cement in a cheap and environmentally friendly way.

Today Denmark even has an accelerator for companies employing people with disabilities; 22 such companies have graduated from the three-year-old Sociale Kapitalfond's accelerator programme, and the fund has invested in another five. "Growing global competition affects marginalised people in developed countries because it takes away entry-level jobs in their home countries," says Lars Jannick Johansen, founder and CEO of the fund. "But we're also living in an age where uniqueness is important. Companies have to provide good service at a good price, but they also have to distinguish themselves, and employing marginalised people is a good way of doing that."

In OECD countries, 19% of less educated people, and 11% among the better educated, have some form of disability. The companies in the Sociale Kapitalfond's programmes, including the Telehandelshuset and Bornholms Mosteri, now employ and train some 730 residents with disabilities.

Around Denmark, the number of people with disabilities employed by private companies is surging. According the national labour agency Jobindsats, last year almost 10,000 Danes with disabilities worked in the private sector, up from just over 5,000 in 2009. The number employed in the public sector is about three times larger.

"The trend took off in 2011 and has grown stronger over the recent years," says Morten Hyllegaard, a director at Copenhagen-based Monday Morning, Scandinavia's largest independent think tank. "Danish companies take social responsibility very seriously, especially regarding the unemployed with mental issues or problems with abuse. Ignorance and prejudice are the main barriers against more companies following the trend."

Danish entrepreneurs have spotted a promising opportunity. "In the past three years we've looked at 450 companies," reports Johansen. "And there's a growing number who're either in this space or want to enter it." Hasemann, for her part, is considering international expansion.