A good deal of attention has focused on the psychological makeup of the man who sought and won the Presidency in 2016, including the provocative “Is Donald Trump a Psychopath” by fellow Cambridge author, Steven M. Stahl. (Stahl’s answer: probably not.) While I don’t expect this line of inquiry to let up anytime soon, I would like to turn to a different psychological examination. What can be said about followers, those people who place their trust, express their faith, and pin their hopes on such strongmen leaders?

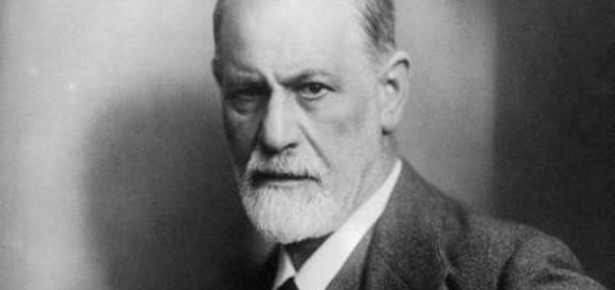

In my recently published Discourse on Leadership: A Critical Analysis, I delved into the writing of Sigmund Freud, and that is an excellent place to anchor a consideration the psychology of followers.

By the time of the 1937 publication of his Moses and Monotheism, Freud had established a worldwide psychoanalytic movement. Over time, intellectual curiosity led him to a broader perspective, seeking to illuminate a linkage between individual psychology and group dynamics, religious belief, and the structure of history. Although the study of Moses represented his most fully realized view of the hero role in history, his notion of the leaders, followers and group dynamics can be traced to earlier works, most specifically his 1921 Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego.

For Freud, the need for a single, special leader was primal, arising from a human drive for dependency and even love. He opened his reasoning by situating the individual within a larger collective: a tribe, clan, or family. This was the unit that proscribed the psychological world of individuals. Freud reflected the gender biases of the Victorian era, placing the father as the central figure in the family unit.

For Freud, group membership conveyed many obvious benefits to individual members, including safety and security. However, by following a single leader, group members tend to bend their thinking “in the direction of the approximation to the other individuals in the group.”[1] Group members would opt for conformity while sacrificing individuality.

In Freud’s treatment of Moses, we can see his most complete statement of the role of the male hero-leader in human society. Freud’s Moses story departed in dramatic ways from that found in the Old Testament. Rather than being a Jewish son sent floating down the Nile, he was an Egyptian born into royalty. His later struggle with Pharaoh was, in this narrative, a struggle – perhaps symbolic but maybe not – with his “real” father. Moses emerged as a hero by rebelling against this father.

Monotheism, which Moses institutionalized among the Hebrews, represented for Freud the triumph of the father figure, the single male deity who could serve as the organizing totem for his followers. Moses was the great man, with monotheism representing the institutionalization of the single male authority figure.

Thus we have a significant refinement of the desire and drive for a great man to lead us. Throughout history, Freud noted, “the great majority of people have a strong need for authority which they can admire.”[2] Individual psychology, family dynamics, and psychosexual drives create a recurring human desire for a single, male hero. This father figure satisfies a primal need for protection and love. That drive, while understandable, even predictable, can also be threatening, even dangerous.

In Freud’s view, the great man leader was “the father that lives in each of us from his childhood days for the same father whom the hero of legend boosts of having overcome.” The “picture of the father,” then, included the “decisiveness of thought, the strength of will, the self-reliance and independence of the great man” as well as “his divine conviction of doing the right thing which may pass into ruthlessness.” The great man will be admired, trusted, and followed. However, “one cannot help but being afraid of him.”[3]

And Freud did not stop with that warning. By admiring a leader unconditionally, followers were submitting to authority. In so doing, followers rendered themselves vulnerable. Submission enabled an authority figure who “dominates and sometimes even ill-treats them.”[4] Writing on the cusp of a World War II, Freud’s warning was tangible and immediate.

And well worth considering today.

[1] Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (New York: Liveright Publishing, 1921/1967), 20.

[2] Moses and Monotheism (New York: Vantage, 1937/1967), 111.

[3] Freud, Moses and Monotheism, 170.

[4] Ibid., 111.

Latest Comments

Have your say!