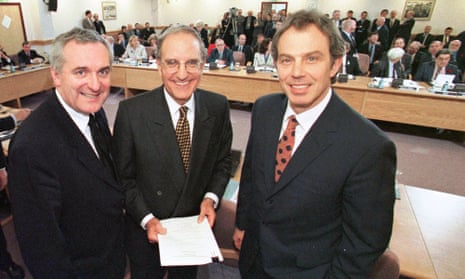

Twenty-one years ago, on Good Friday 1998, we put our signatures to the agreement to end the conflict in Northern Ireland. Our names, as prime minister and taoiseach, on that document were followed by individuals from across the political spectrum in the UK and Ireland who had worked so painstakingly towards peace. The Good Friday agreement was a monumental moment for our two countries, and the people in both countries seized the opportunities it presented.

But when we felt the “hand of history upon our shoulder” on 10 April, 1998, it was pushing us to the start of a process, not signalling the end of one. In our eyes, the people of Ireland, north and south, have been signing that agreement every day since. Because it is the everyday actions and interactions of people, businesses, civil society, politicians and governments that enable a lasting peace, not signatures on a piece of paper.

That is why we feel duty-bound, a generation on, to stress to Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn the ongoing significance of the Good Friday agreement, to add context to the Brexit debate and to set out our shared view of what should happen to protect peace and prosperity, between now and the newly announced EU “flextension” to 31 October.

First, May and her colleagues in parliament must learn from previous mistakes and use this extension to encourage calm amid the chaos. Over the next six months it is likely that elements within the Conservative party will seek to oust her and push for a new prime minister to fight for what they call a “proper Brexit”, the details of which have never been spelled out by Boris Johnson or anyone else. Whatever criticisms people may have of May, her party should reject such manoeuvring. There will be local elections, almost certainly now European elections, and Britain will soon enter its fourth year since the 2016 referendum. Conversations between campaigners, politicians and the public will at times be difficult. But politics is always full of difficult conversations. The important thing is to get to the right place in the end.

Of all of the meetings we were involved in leading up to the Good Friday agreement, none were more difficult than those with family members of victims of the Troubles. Widows of British army soldiers and RUC officers, sons and daughters, wives and husbands, mothers and fathers of nationalists, republicans, loyalists. There were those who could not understand why we were seeking a deal with people who had killed their loved ones, or releasing from prison people who had committed horrendous crimes. Yet there were also those who made us promise to make the process work to ensure that others would not have to go through what they did. These conversations made us determined to ensure that such courage would form the basis upon which those following could build a better future.

Yet in practice, it was also time away from these conversations and from the media storm that enabled the Good Friday agreement to come together. It was time in the company of rivals with differing versions of what was right, and what was wrong, what was possible, and what was not; people with the personality and resolution, when surrounded by uncertainty and competing visions of the future, to put together a new power-sharing agreement.

Of course, nobody should compare the tragedy of the Troubles to Brexit, but as the rhetoric becomes stronger, the language becomes more divisive and inflammatory, the divisions in the Tory and Labour parties more evident, the need for calm matters even more. Having conversations with the public matters. Speak to those who voted remain, the 48%, alongside those who voted leave, and try to understand both. Speak to those who do not tweet incessantly or rage endlessly on radio phone-ins, as well as those who do. Understand that the public are undergoing the same process of churn and reflection as the politicians, and give them permission to be honest about that. Getting away from the media chaos to do this matters. Getting the right personalities together from across parties matters. Teams of rivals must be built.

For some the defining image, and in some ways crowning moment of the Northern Ireland peace process is that of Ian Paisley, the loyalist politician and Protestant religious leader laughing and smiling alongside former IRA leader Martin McGuiness after they became colleagues. Even we, back in 1998, as we signed the agreement, with Paisley baying “treachery and treason” at the gates, could not have dared imagine that a decade later Paisley would be first minister of Northern Ireland, and McGuinness deputy first minister.

At Martin’s funeral in 2017, Bill Clinton said about him that he had “expanded the definition of us and shrunk the definition of them”.

On Brexit, it is time to do the same; to elevate the discussion above individual interests to the collective, to expand the definition of us and shrink the definition of them. It is also time to be brutally honest about the real choices and their consequences. There is no variation of Brexit that can strengthen the relationship between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. There is no variation of Brexit that will grow the UK economy any time soon. Brexit, particularly a no-deal Brexit with the risk of a hard border, is both the most serious threat to the Good Friday agreement since it was created, and to the union in our lifetime. It is time to acknowledge the reality of these challenges and to work collectively to overcome them. It is our belief, or at least certainly our fervent hope, that the Good Friday agreement will survive Brexit.

The acceptance of the principle of consent in the Good Friday agreement was a unionist/nationalist trade-off allowing the majority of people in Northern Ireland to stay part of the UK if they wished, while also enabling aspirations for a united Ireland to be heard. Out of that came the power-sharing agreement, a new Northern Ireland police force, changes to the criminal justice system, and the resolution of a whole lot of cultural, symbolic questions.

Part of that nationalist aspiration is to have an open border between north and south; which then leads to broader questions about single market access and a customs union. Therein lies the problem. It is no coincidence that several universities and thinktanks are now examining what a united Ireland would mean and how it would happen. You cannot walk around the island of Ireland without being asked about the future of a united Ireland – and that has resulted from the position on the border taken by Brexiteers.

It is precisely because of such issues as the border that there should be a confirmatory vote on whatever now emerges from the Brexit process in parliament. The Irish border question is a metaphor for the entire negotiation. It is not possible for the UK to have frictionless trade with the EU if it remains outside the single market, so the question is how much friction is compatible with the Good Friday agreement, and that in turns defines any Brexit agreement that will pass through parliament.

Such is the variation of Brexit deals that have been debated, and the vastness of the Brexit promises made in 2016, that any agreement is unlikely to be what the public voted for. The UK people should have the final say. They should be asked if now, knowing all that they do, they still wish to proceed, on whatever basis is agreed by government and parliament.

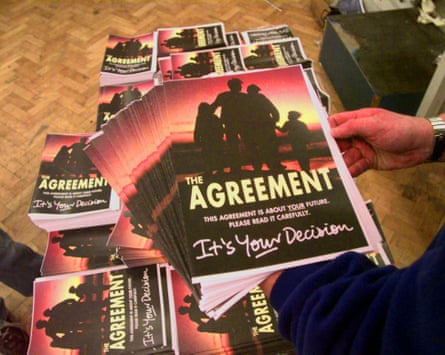

Following the Good Friday agreement, there were two referendums. The referendum in Northern Ireland, on the agreement, based on facts not promises, clarity not ambiguity, received a 71% yes result. The related referendum in the Republic of Ireland achieved a 94% yes. There is now time for a confirmatory referendum given the EU has expanded the Brexit deadline to 31 October. It is this that must be pursued, and May should take the lead in that process.

It was not solely through the signatures we scribbled on 10 April 1998 that peace came to Northern Ireland. It was the values people ascribed to it as a result. Reconciliation. Tolerance. Mutual trust. Respect for the views of others. A shared desire to reach the right conclusion on terms that all but the most extreme can live with and accept. That is the approach needed on Brexit now. The extension gives us another chance. We must not waste it. We must use it wisely, and deliver the three Cs – calm, clarity and a confirmatory vote. Only then can come the fourth C: closure.