How NH Defied the Feds, Mob and Church to Create the First State Lottery

In 1964 we hosted the first state-run lottery at Rockingham Park in Salem, a horse race that sparked a national sensation and scandal and put us in the crosshairs of the mob, media and the church.

The final turn of the scandalous, controversial and ultimately wildly successful sweepstakes race at Rockingham Park in Salem. Photo from the Union Leader collection at the Manchester Historic Association.

Just before the bell went off at Rockingham Park racetrack, Frank Malkus of Carteret, New Jersey, took out a fresh cigar, put a match to the tip and sucked life into it. Eleanor Malkus, in double pearls, held her white-gloved hand in her husband’s.

A 21-year-old co-ed, wrapped in a heavy, blue coat, peered across the track with a pair of binoculars. Carol Ann Lee of Worcester had never been to a horse race, so she brought her father, friends and kid sister. She wondered if she was about to turn a three-dollar wager into a $100,000 payoff.

The VIP section at Rockingham held about 20 people and a gaggle of reporters and photographers looking to record their every reaction.

“Well,” Malkus said, puffing the cigar. “Here it goes.”

It was nearly 5:50 p.m., September 14, 1964. Thousands were in the grandstand and millions watched at home on “ABC’s Wide World of Sports.” When the metal gates flew open the New Hampshire Sweepstakes would finally be underway — the last step in determining the winners in the first state-run lottery in the United States.

It was the culmination of a national sensation and a national scandal — an all-out effort by the federal government to derail the Sweeps at the same time tens of thousands of people were trekking to state just to get a ticket. The proposal for a first-in-the-nation lottery spawned a debate about the very character of New Hampshire, the likes of which had not been seen before or since.

In today’s era of scratch tickets and nine-figure Powerball jackpots, it’s easy to forget that state lotteries did not exist before the Granite State’s bold experiment. In fact, lotteries were illegal — and the creation of the New Hampshire Sweepstakes put the state on a collision course with the FBI, the IRS, the FCC and the Post Office. It also put the state in the crosshairs of the media, the church and the mob.

The Sweeps were not the kind of lottery we think of today. It was not a numbers draw or a scratch ticket. It was a horse race. In this two-step process, selected ticket holders were matched to a thoroughbred. If that player’s horse won the race, they’d get the jackpot.

In the 1700s and 1800s, colonies and states sanctioned lotteries to raise money for everything from the Continental Army to the dorms at Dartmouth — but these lotteries were always conducted by private brokers and never the government. Skimming cash and other forms of cheating by ticket sellers became commonplace. Bare-knuckle boxing and cockfighting were considered “gentlemanly” but — in the words of the US Supreme Court — “comparatively innocuous when placed in contrast with the wide-spread pestilence of lotteries.” In the 1890s, Congress finally enacted measures to outlaw such games.

After the New Hampshire House and Senate passed the sweepstakes bill in April 1963 — a legislative task 10 years in the making — John King spent two weeks alone in his office deciding whether or not to veto the bill. He was flooded with letters and telegrams; opinion was split down the middle. King read a letter from a woman who was “stunned and sickened” at the idea of the government resorting to gambling to pay for education. In the same pile was a note from this very woman’s husband praising the idea of a sweepstakes.

Gov. John King (right) with Rep. Larry Pickett (left), who got the sweepstakes bill signed into law. Photo from the John King collection, NH Institute of Politics.

“Governor,” he begged, “don’t answer this letter.”

The major obstacles to a sweepstakes were federal rules prohibiting lottery material from the mail and laws against transporting gambling paraphernalia (like tickets) across state lines. Also, the Justice Department had publicly announced its fear a lottery would attract racketeers who would infiltrate and corrupt the operation.

In secret meetings with the DOJ, King’s staff determined operating a lottery within New Hampshire would be permissible. But the FBI would take action if tickets crossed the border — an inevitability nearly impossible to prevent (and greatly encouraged).

Governor King signed the Sweepstakes bill to great fanfare on April 30, 1963. Nearly every state newspaper editorial writer got into a lather about it, fearing, as the Enfield Advocate put it, “New Hampshire is sure to get a bad name out of the Sweeps.”

The media criticism was unrelenting. As stated in the Somersworth Free Press, “The work of a generation has gone into building an image for this state — of a place where families can enjoy the natural beauties of our outdoors, where industry can come and grow in a healthy economic climate, where young people can live and find opportunity for growth of their interests, where our aged citizens can retire and live in quiet and peace of mind. Now, almost overnight, all that is to be wiped out.”

Gov. King shakes hands with Ed Powers after swearing him in as the first executive director of the NH Sweepstakes. Photo from the John King collection, NH Institute of Politics.

“What is happening to New Hampshire’s image at the hands of politicians,” cried the Lisbon Courier, “shouldn’t happen to a dog.”

Even Reader’s Digest asked rhetorically, “Is either New Hampshire or Uncle Sam so hard up that this shabby dodge is the only way out? …. It will mean moral bankruptcy for New Hampshire.”

The only editorial opinion that meant anything in New Hampshire belonged to Manchester Union Leader publisher Bill Loeb. He favored the Sweepstakes because he feared without it the Legislature would pass a sales tax — something he abhorred over all else.

Pointing to the state’s reliance on so-called “sin taxes,” Loeb penned the strongest defense of the lottery yet. “No one has to go to the track and bet. No one has to smoke tobacco. No one has to drink. But how do those who oppose the Sweepstakes propose to raise the money? Either a sales tax or a property tax or some other kind of levy that people will have to pay, even though it will hurt them dreadfully to do so.”

Letters of support for the Sweepstakes flooded into King’s office, a colorful mix of desperation and pluck. A cheeky gambler penned, “Can these be sent through the mail, or carrying pigeon, just put the tickets in a box and mark ‘write-in vote’?”

Everyone, it seemed, wanted a piece of the action. More than $200 a day in unsolicited cash came from around the world from people asking for tickets (even though sales were nearly a year away). King and Millimet weren’t even sure if they could legally mail the money back.

The first legal lottery ticket of the 20th century being purchased by Gov. KIng. Photo from the John King collection, NH Institute of Politics.

They couldn’t sell, advertise or promote the lottery outside of the state. If these thousands of people wanted Sweepstakes tickets, they’d just have to come to New Hampshire.

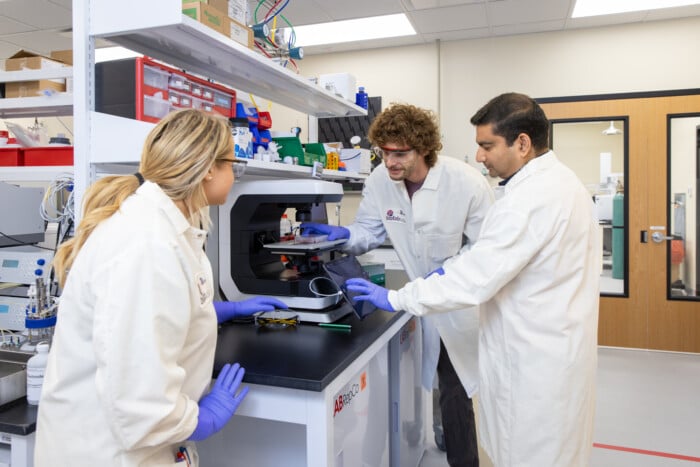

The ticket idea had come from Edward Powers, the first executive director of the New Hampshire Sweepstakes. Powers was head of the Boston FBI office and one of the most famous G-men of his day. He cracked the 1950 $3-million Brinks Heist (the largest bank robbery in history) and was the first to capture two of the FBI’s most wanted fugitives at the same time. Powers’ unimpeachable reputation quelled fears of mob infiltration.

Powers ordered construction of special ticket machines. Players would sign their names to a slip and the machine would spit out a carbon copy, the original ticket staying in the machine. The person whose name was on the ticket — not the person in possession of the slip — would be the Sweeps winner. The state argued the copies were not needed to conduct the lottery; therefore, they did not meet the federal definition of “gambling paraphernalia.”

The Justice Department, however, wasn’t buying it. People in Rhode Island, New York and New Jersey were all arrested for being in possession of New Hampshire lottery tickets.

Sweeps tickets went on sale March 12, 1964, at Rockingham Park. In a ceremony of much fanfare, Ed Powers sold the first $3 ticket to Governor King: #0000001. He held the slip high — the first legally purchased lottery ticket in the modern age — and the gathered crowd exploded into cheers. Then the rest of the sales windows opened and a crush of dreamers kept clerks working until one hour after the track was supposed to close.

A speech before the first Sweepstakes drawing by Gov. King. Photo from the Union Leader collection at the Manchester Historic Association.

Mary Macy of Malden, Massachusetts, purchased nine tickets, one for herself and each of her eight friends. “I want a white convertible, a summer camp on the water and a boat that sleeps three or four people,” she said while leaving the window. “But, most of all, I want a heart operation for my son.”

A reporter for the Concord Daily Monitor tried to quiz ticket buyers why they wanted a piece of the action. “Well, you see it’s this way, Doctor Kildare,” replied one guy chewing a cigar. “I like to build schools … nice, big schools.”

A clearly annoyed player said, “Are you a cop or a nut? Get outta here. I do it because I’m charitable.” Someone in the back of the line yelled at the journalist, “Buddy, why don’t you be a good guy, shuddup, and buy a ticket?”

In July, a pair of beauty queens pulled names from a rotating 2,400-pound Plexiglas drum and matched each one with one of the 332 horses hoping for a position in the race. For every $1 million in tickets sold, another batch of players and stallions would be drawn. In the end, there were six people whose fortunes rode on each horse.

Among those selected to win prizes both large and small were an 8-year-old boy, a recently deceased immigrant, an office pool from New England Telephone and someone who signed the slip “Old Man Sunshine.”

Left: Finalists, including Carol Ann Lee, in the New Hampshire Sweepstakes watch the race from a VIP area. Right: Big prize winner Carol Ann Lee took home $50,000 and became a media darling. Photos from the Union Leader collection at the Manchester Historic Association.

Governor King’s favorite winner was Elizabeth Perkins. She was the wife of former Senator Raymond Perkins, leader of an anti-Sweeps action committee.

By the time all of King’s horses were off, New Hampshire sold $5.7 million in $3 tickets. Just before the race, the governor declared, “This is the most popular thing since the Revolution.”

Though the Sweepstakes would never obtain the same level of interest as its inaugural year, and would be replaced a decade later by scratch tickets and daily number games, New Hampshire’s effort kicked off the modern lottery age. If New Hampshire had failed, no states would have followed. Today there’d be no mega-jackpots, no overnight millionaires. If so, what would be our American Daydream?

10 Things You Didn’t Know Were Paid For by a Lottery

By Kevin Flynn

Lotteries — some legal, some not — have been around for centuries and have served as a popular method for raising funds for various causes and public works projects. Here is a list of things that likely would never have been built or accomplished without lotteries — the original crowdsourcing campaign.

1. The Great Wall of China – Around 200 BC, the Western Han Dynasty used a lottery to pay for repairs to and expansion of the Great Wall. They created an early form of Keno called the “white pigeon game,” named for the birds that carried results from village to village.

2. The roads to Rome – All roads may lead to Rome, but not all roads could be maintained without spare change from the plebeians. Booty from military conquests were raffled off, the proceeds going toward Imperial infrastructure.

3. Voltaire’s academic career – In the 1700s, a French national lottery was created after the bond market collapsed. To encourage bond purchases, lottery tickets were awarded against a fractional percentage of the purchase. Voltaire and his friend, mathematician Charles Marie de la Condamine, discovered a mathematical flaw in the program that allowed them to purchase large quantities of tickets with cheap bonds. Before the government caught on, Voltaire made enough on his winnings to live comfortably while pursuing philosophy.

4. Jamestown colony – In order to finance the privately held Virginia Company of London, King James I granted the company the authority to hold a lottery to raise funds for a grand exposition. Proceeds were used to create Jamestown, the first English colony in the New World. You can say the America itself is the offspring of a lottery.

5. The Ivy League – How did these frontier colleges become the elite learning institutions of America? During the 1700s, many of them raised money for new buildings or dormitories through lotteries (some running them multiple times). Among the schools that relied on games of chance to build their campuses include Yale, Harvard, Dartmouth, and the forerunners to Columbia and UPenn (whose motto was “Laws without morals are useless”).

6. The Continental Army – Running out of money to continue its revolution against the Crown, the Continental Congress authorized a national lottery to raise cash for the fight. General Washington bought the first ticket. It fell far short of its $10 million goal, but individual colonies did well financing their militias with lotteries. Massachusetts earned $750,000 to provide bonuses for new volunteers.

7. Faneuil Hall – Because the early states had trouble collecting taxes and the bonds they issued were weak, many communities relied on legal gambling to pay for public needs. Proceeds paid for canals in Pennsylvania, aquifers in Kentucky, bridges in Connecticut, and fire-fighting equipment in St. Louis and Detroit. When Faneuil Hall, one of Boston’s most iconic landmarks, was leveled by fire in 1761, John Hancock helped organize a lottery for its reconstruction.

8. The estate of Thomas Jefferson – Deeply in debt at the end of his life, Jefferson petitioned the Virginia legislature to allow him to run a personal lottery with his effects and landholding as prizes. Jefferson had always been a supporter of lotteries, describing them as a tax “laid only on the willing.” However, before he could run his lottery, Jefferson died and these items were instead sold at an estate sale.

9. Washington, DC – Congress approved a $100,000 jackpot in the 1823 Grand National Lottery, profits of which were to be put toward restoring and expanding Washington, DC. After the winners were drawn, the broker contracted to conduct the lottery absconded with all of the proceeds — never to be seen again. The grand prize winner sued and the US Supreme Court ruled that the federal government had to pay up.

10. The Irish Republican Army – Popular around the world between the 1930s and 1960s, the Irish Sweepstake purportedly raised money for the Irish National Hospital. Although illegal in dozens of countries, the cops didn’t crack down on ticket sellers and the newsreels loved stories about instant millionaires. The Sweep was run by former IRA leaders who smuggled into Ireland the outlawed tickets and cash in the same boats and planes alongside rifles and ammunition for the Irish rebels. Also, ticket sellers skimmed money from sales to give to the IRA. It’s estimated only 10 percent of the hundreds of millions of dollars in Sweep proceeds ever went to the hospital.

Learn More

Learn More