Cognition

Come Into The Garden: Hidden Issues With Expressive Language

Expressive language issues and social issues are often related.

Posted August 5, 2012

Some time back, my mother and I were reminiscing when she mentioned something that brought me up short. She was remembering some of our earliest visits with my maternal grandmother. “You were so charming,” she said, “You kept running to the back door. In your chirpy little voice you’d call to us. You’d say, ‘Come into the garden! It’s a beautiful day!’”

My mother seemed a bit surprised by my reaction – she clearly didn’t think anything of it. To her, it was a typical thing for me to say. It was simply one of her cherished memories of my quirkiness.

But knowing what I know now, I have to wonder if there wasn’t more to it. Outside of being a bit precocious (by her own report, these visits took place when I was three and five years old), there something else that’s a bit odd about it: There was no garden.

My grandmother lived in the middle of the desert. Outside the back door was a concrete patio. Beyond that, nothing but desert for miles. So what was all this talk of gardens?

I may never know for sure, but I have a theory. When I think about it, this statement makes sense only in the context of my mother’s love of British culture, literature and TV. One of the earliest pieces of music I can remember learning was the theme to Masterpiece Theatre.

In British parlance, the word “garden” is used in the same sense that Americans use the term “yard.” Is it possible that I “lifted” this bit of language from one of my mother’s British television shows? If this theory is true, this means what I was displaying a form of delayed echolalia. I was saying, “Let’s go outside!” – but borrowing other peoples’ words to do it. Something not un-precedented in my family.

This little discovery from my childhood is exemplar of a truth that is not uncommon among those whose autism was not diagnosed in childhood. Just because expressive language issues were not caught in childhood, doesn’t mean they weren’t there. For many of us, they were simply a little more subtle.

Not all seem to believe this is so. Back in February, Dr. Paul Steinberg wrote an op-ed for the New York Times in which he questioned the increasing diagnoses of Asperger’s, especially among those who were diagnosed late in life. The basis of his argument? “True autism reflects major problems with receptive language (the ability to comprehend sounds and words) and with expressive language.” And, apparently in his opinion, those of us with Asperger’s do not fit the bill.

Many adults with the diagnosis would say otherwise – in fact, difficulties with expressive and receptive language are the root cause of a number of aspects of the “social disabilities” he claims are segregated from “true autism.” This week, a friend and fellow adult on the spectrum opened a thread on Facebook. How many other adults diagnosed late in life, she asked, had discovered that they had expressive language issues?

The resulting conversation was lively. The consensus: Absolutely they had. And the ways such difficulties manifested themselves was widely varied. For myself, I can think of countless examples. Problem is, many of them are not immediately apparent to another person. They are buried beneath layers of coping mechanisms, developed over years. But, if you know what to look for, they are there.

One day, I visited a local diner with my husband and my grown stepson. We are frequent customers, but it is always a little bit stressful for me. It’s popular and loud, and the menu is like a book. Worse, the soups and sides change each day, and are rattled off by the wait staff at the beginning of each visit.

This particular visit was at one of their peak times, thus the noise was higher than typical, ensuring trouble from my auditory processing issues. I tried to follow as closely as I could, but I was quickly overloading. I struggled to make sense of what was being said.

Beyond that, I was struggling with the working memory task that required my keeping the laundry list of options in my mind while also using a portion of that memory to make the decision which items to choose. My brain felt like a full bucket of water, threatening to overflow. Finally, trying to stem that tide, I squeezed my eyes shut and burst out, “Chicken soup and corn, please.”

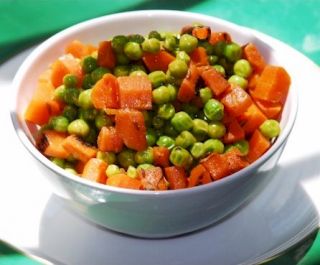

At least I thought I did. But when my food came I learned differently. I found myself staring at a bowl of peas and carrots. I hate carrots, and would never have ordered them voluntarily. (I never much cared for the texture, and the experience of nearly choking to death on them my first year in Kindergarten did nothing to warm my heart.)

But, when I challenged the waitress, she responded with confusion: “This is what you ordered.” My response was immediate. “No, I didn’t.” Then my stepson spoke up. “Yes, actually you did. I heard you.” I was embarrassed, and a bit surprised – but I realized it was probably true. I heard my husband let go a deep sigh beside me.

He’d been through these situations before and it had caused terrible fights between us. Before I knew what was going on, before I realized the extent of my expressive language issues, I would often fight hard when people challenged me. It’s understandable – from the standpoint of the speaker, it feels like gaslighting.

It’s a massively disorienting feeling. You KNOW what you said. Unfortunately, what you come to learn is that the words you thought are not the words other people hear, or the words your mouth forms. Something gets lost in the translation.

On the other side of it, it’s just as disorienting…because the other person KNOWS what they heard. The upshot of the interaction is that you’re perceived as dishonest, deluded, or worse. Both people end up feeling deeply invalidated – and it appears that the other is to blame.

Expressive language issues are often under-recognized in adults on the spectrum, but they cannot be underestimated as far as the challenges that they create. They are issues that often hide in plain sight. When it comes to these issues, what you see on the outside is often different than what’s underneath. This is a point that people need to understand.

It’s important not to judge a book by its cover.

For updates you can follow me on Facebook or Twitter. Feedback? E-mail me.