How a Guy With a Wooden Leg Won 6 Olympic Medals

Another amputee beat Oscar Pistorius to the Olympics... by 108 years.

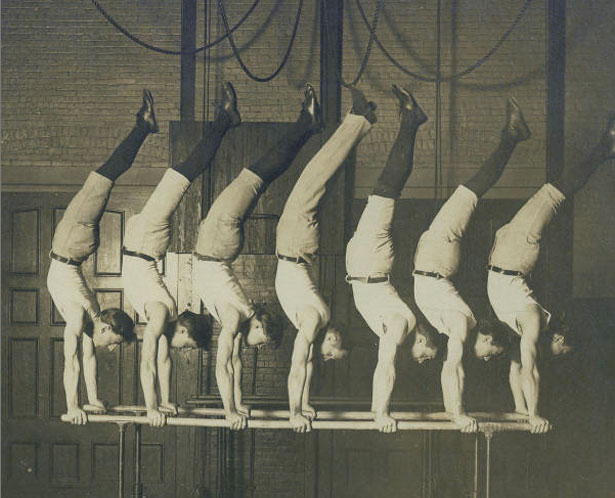

Meet George Eyser. He's the one in the center there, wearing khakis as he holds himself upside down on the parallel bars. Eyser won six medals in the 1904 Olympics, including three gold medals. He had one flesh-and-blood leg. The other was amputated below the knee and terminated in a wooden prosthetic.

He is quite obviously the forebear of Oscar Pistorius, the double-amputee sprinter, who competed in this year's London Olympics.

The totally understandable tendency when we hear about Eyser or a Pistorius is to go straight to the Great Man theory: "Wow! That guy is a a hero!" And Eyser is obviously tremendously talented. Let's even go with heroic. But I couldn't help but wonder: how does a guy with a wooden leg get all the training to be an Olympic champion, even in the decidedly more amateur and amateurish games of those days? What were the structures and circumstances that helped him fulfill his astounding potential? Who helped him "build that" body and skill set?

And to tell that story, we have to start with Napoleon.

No, seriously, Napoleon, the military genius and notoriously short man from France. Turns out that in the early 19th century, when the French army was running roughshod over all its European neighbors, a guy named Frederick Ludwig Jahn, aka "Father Jahn," whipped up a frenzy among the Germans to train their youth in the gymnastic arts. His story gets complicated quickly as many later thinkers and writers implicated him as one of the influences that came together to form Nazi thought. But the organizational infrastructure that he created -- the Turnverein, or gymnastics club -- moved out of his control and became very strongly associated with the radical political movements that attempted revolutions in 1848. Yes, gymnastics clubs as revolutionary machinery. Believe it.

"The aftermath of the 1848 revolutions devastated the German gymnastic movement. Clubs were disbanded, property confiscated and leaders lost to jail or exile," one academic Encyclopedia of the revolution summarized. "The various attempts to form a union of gymnastic clubs likewise fell victim to the Reaction. In these circumstances, the Turnverein turned away from politics to concentrate on its gymnastic program."

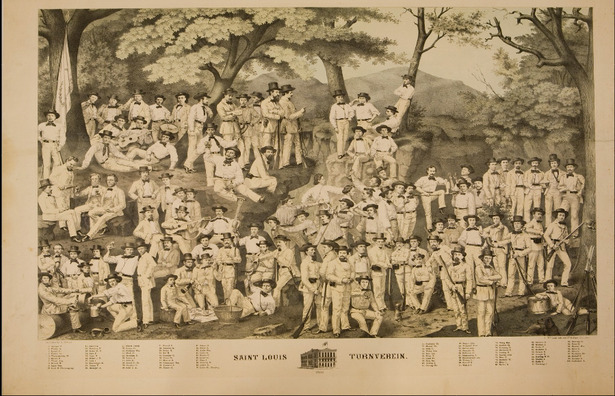

But Germany's loss was America's gain. When emigrants arrived in the new world -- say, in St. Louis -- from the German states, they brought the tradition of the Turnverein with them. They were, as one local St. Louis historian put it, the "centers of all that is best in German life. They foster not only physical culture, but race patriotism and love of the old mother tongue."

As the impending war approached, St. Louis's German community comprised a strong core of Union support within the city. Members of the Turnverein, or Turners as they were called, met at Turner Hall, their meeting place on Tenth Street, and resolved to "stand fast by the Union, endorse the present administration in its attitude against secession and...defend the flag with their life's blood." They used Turner Hall to store arms and recruit members into Home Guard units.

The Encyclopedia of the History of St. Louis, written in 1899, gives a more colorful description of the Turners' war effort:

The same ardent desire to free the slaves animated the Germans at that time throughout the country; for the most part political refugees themselves, they were pledged to liberty everywhere. As a result, entire companies of volunteers, and almost entire regiments were made up almost excluslive of Turners; thus the Seventeenth Missouri was frequently referred to as the Western Turners' regiment.

But back to the story of Eyser's triumph. He was a part of the Concordia Turnverein, located in the southern suburbs of St. Louis. The Concordia was one of 11 gymnastics clubs or Turner halls in St. Louis alone in the late 1890s and one of 314 such societies around the nation.

Like so many fraternal organizations, they peaked in the years around the turn of the century, at which time there were 314 societies in the Nord Amerikanischer Turnerbund, or North American Gymnastics Union, and tens of thousands of members.The St. Louis Turnverein were apparently a site to behold.

"The German Turners are all tall, husky-looking chaps, each being at least 6 feet tall, weighing on an average of about 185 pound," one St. Louis paper reported. "It could plainly be seen when one of the turners left the apparatus if he was a member of the German team or not, as each of these stood erect as an arrow when through with his exercise."

So, what we have in Eyser is not just a story of individual achievement but a deeper, more complex tale of the way an idea can translate into the social infrastructure that can help produce remarkable results. You can't take anything away from Eyser, but we should remember the organization that provided his training, support, and ideology under what must have been quite difficult circumstances. After all, he wasn't a wealthy man, working as a bookkeeper for most of his life -- until he vanished from the history books, a mere six years after his six medal-winning performances.

* The title of this post has been updated to reflect that Eyser won six Olympic medals (including three gold), but not six *gold* medals. We regret the error.