Before your trip abroad, you hit the flashcards hard. You memorized how to say essential words and phrases like “hello,” “where is the bathroom,” and “I’ll have a beer.” But once you arrived, it’s like your brain had never encountered the language at all. Words would not come.

It’s not you, it’s how you used the flashcards: Learning a language as an adult takes time and effort, but the go-to study methods that most diligent language-learners use are out of date by about hundred years.

There is a moment in every modern language learner’s studies when they discover spaced repetition systems (SRS) and think, “I have been wasting a lot of time by not doing this.” SRS is a learning system that makes the nitty-gritty of studying hundreds of new pieces of information—say vocabulary words—more efficient. If you’re learning a language, you should be using it.

Good news: Spaced repetition also uses flashcards! There are two things that set it apart from cramming Spanish vocabulary words for a couple weeks before going to Mexico, though. Those two things are right in the name: “space” and “repetition.”

The forgetting curve

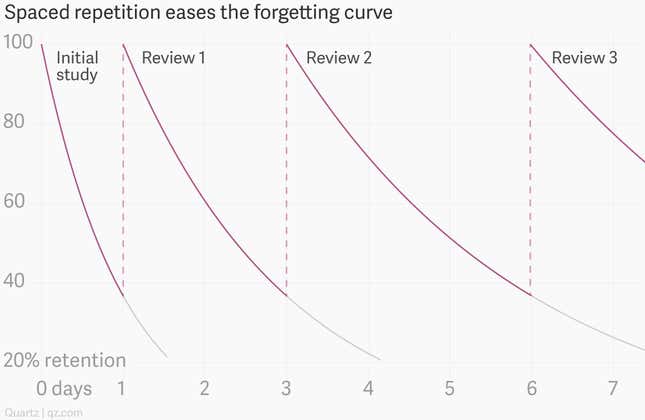

Fundamental to the theory of spaced repetition is the idea of the “forgetting curve,” thought up by the German psychologist Herman Ebbinghaus in the late 19th century. Think of this as the evil twin of the learning curve. It describes the rate at which you forget something once you learn it, either for the first time or after reviewing. There is even a formula for it.

The forgetting curve slopes steeply downward after you first learn something. New material tends to not stay around for long. This points to why cramming is a bad way to learn. It might help you pass the exam, but you will soon forget everything you were tested on. Luckily, the curve can be softened by reviewing the information at particular intervals. That is to say, spaced repetition.

This chart uses a modern version of the formula to show how the curve eases after repetitions.

Using spaced repetition might mean that you study a flashcard for a new vocabulary word and review it the next day. For each review, you will indicate how well you remembered that card, perhaps on a scale of 0 (completely forgot) to 5 (remembered perfectly). Then you will review that word again after a period of time, based on how good your memory of it was. If you completely forgot it, you might see it again the next day. If you remembered it perfectly, it might be a month before that card appears again. Studies have shown that, even in animals, spaced repetition works better than trying to learn large batches of information at once.

The rules

So you’re convinced (I hope) that spaced repetition works. Here are the rules to follow to get the most out of it for learning a language.

- Use software to store and keep track of your cards

- Review your cards once every day

- Make your own cards, and make them your own

- Add context to your cards

Rules 1 and 2 are the basis of SRS. You might ask at this point why you shouldn’t use something like Duolingo, a popular language-learning app that has spaced repetition built in to its curriculum. The answer lies in rules 3 and 4. They may seem optional, but as I’ll explain, making your own cards and personalizing them will greatly increase your ability to remember new material and learn things that are important specifically to you.

1. Spaced repetition software

The spaced repetition algorithm is pretty simple, and there are ways to use the system without the help of software. But using a computer or device is better for a few reasons. It makes it easy to create and edit cards, and to use other tools to add context to those cards. Most importantly, it makes it less tedious for you to get going with a review session.

One of the most popular SRS programs, and the one I recommend, is Anki. It is open source (meaning it’s free), extremely flexible, offers cloud syncing for your flashcards, and has solid mobile apps. There are certainly alternatives. One is Tinycards, an SRS app made by Duolingo. Then there is Memrise, a flashcard app and community with tons of pre-made flashcard decks. Finally, there are some options that only cover a few languages, like iKnow for Japanese or Pleco, a Mandarin-English dictionary app that has SRS flashcards built in.

The advantage of Anki is its flexibility. It requires a bit more work for you, but that allows you to make the cards your own, the way you want them. Want to include example sentences? Go for it. Think images make it too easy? Take them out. Need to create separate decks for grammar and vocabulary? You can do that. Want to take a deck somebody else made and modify it? Anki makes it easy. Feel like the program is giving you too many or too few new words? Change it.

I won’t get into the technical details on how to use Anki, but the manual is helpful and well-written.

2. Review once a day

This is not as difficult as it seems. Your reviews will not take more than 20 minutes or so. If it starts to feel overwhelming, don’t be afraid to reduce the number of new cards the software is giving you. Five words a day is not as good as 10, but you can still learn a lot at that rate. And you will actually learn over time.

A perhaps strange tip on how to get the most out of the review: Make it about more than just processing information. Let’s say the flashcard is a word you know fairly well. Try to get a feel for it. Imagine yourself saying this French word to a French person in France. Try out different ways of pronouncing or emphasizing it. Swirl it around in your head like a fine Bordeaux. If you don’t know the word, think of a mnemonic that might help you remember it next time, or write out a sentence using it.

3. Make your own cards

Anki, Memrise, Tinycards, and other services have hundreds of pre-made flashcard decks for language learners. On Anki, for example, there is 5000 Most Frequently Used Arabic Words w/ Audio, Hangul (Korean Alphabet), and Tagalog for beginners. It is tempting to grab one of these and start SRSing, but you should try not to do that.

There are two reasons why. First, the act of making the card helps you remember the stuff on it. As you’re making the card, think about the term you are adding, how you might use it, when it might be important, and so on.

Second, the way you learn and the things you care about are unique to you. If you are studying Arabic in order to talk to your in-laws, many of the 5,000 most frequent words are probably less useful to you than some rarer ones, perhaps related to your profession or the area where they live. Making your cards ensures they are relevant to your world.

Ideally, your cards will be based on things that have happened to you in your normal life. If you are an intermediate or advanced learner, you might add a new word you heard on a radio broadcast. If you’re a beginner, you may have been curious to know how to talk about your interest in photography and looked up a few related terms. Or maybe your in-laws kept using a harsh-sounding word to describe you, though luckily it turned out to just mean “tall,” and you added it to your flashcard deck. The more you can think of the stuff on the flashcard as being part of real life, the easier it will be to learn, and the reason for learning it will be clearer.

4. Add context to your cards

Making your own cards means you have total control over them. And that means you can add any information that will help you remember what it says. Here are some examples of things you might add:

- An example sentence, especially if you have the sentence you first spotted the word in

- Where you first came across the word—in class, in a book, from a friend?

- Audio of the word being pronounced

- A mnemonic you came up with to remember it

- The word’s etymology

Most of this extra info should be added to the back of the card, where the answer is. The front prompt should always just be the word, or perhaps an example sentence, so long as it doesn’t give away the answer.

Doing this again helps you to think of the word in the real world. An example sentence gets you thinking about not just what it means, but how to use it. Thinking about where you first came across it reminds you that it exists outside of your spaced repetition app. The word’s etymology shows that it is part of a system of language. The goal is to not just think of words—or grammar points, or whatever you’re studying—as isolated bits of information. They are part of a living language.

Go forth and SRS

Learning a language can be frustrating. Progress often feels slow. Part of that is because there is a lot to learn. But part of it is also that language education often does not utilize the best methods out there.

Spaced repetition alone is not enough. Don’t expect to blast through 2,000 vocabulary words and be able to use them intelligibly. SRS is a tool for reinforcing the things that you know are important for your language learning, like words you come across often or grammatical structures that seem useful. It is no replacement for talking to people in the language you want to learn, writing practice, or reading words in the context of a story or article.

But it makes the process of remembering those things much easier and more effective. You will not be studying words only to forget them later. You will not be reviewing words you already know well. The rules I outlined above came from my years becoming fluent in Mandarin in Taiwan, when I was constantly evaluating and re-evaluating learning methods. Two things I learned: Spaced repetition works, and context makes it work even better.