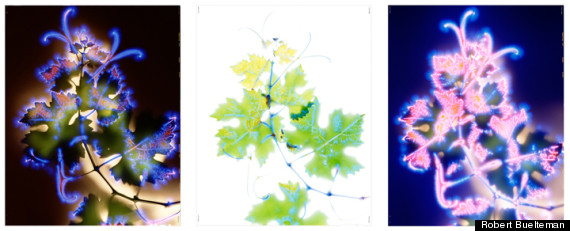

Robert Buelteman is not your average nature photographer. The California-based artist shocks flowers and plant life with thousands of electric volts, capturing an entrancing image of the energy streaming through them.

The photographer's method has roots in Kirlian photography, a process from the 1930s that is also known as "electrography." First Buelteman carves at his plant specimens with a scalpel until they are sheer and then places them atop a metal sheet in between Plexiglas, surrounded by liquid silicone. He then channels his inner mad-scientist and passes an electric current through the plant using a car battery. The electrons shoot from the metal and through the skeletons of the translucent plants and Buelteman catches them by painting with a fiber-optic cable. The cable captures the glowing strands of light pulsing through the plants, by emitting a beam of white light, about the size of a human hair. This image is then transferred onto film. The gas around the plants ionizes when the plant is shocked, spurring a mystical blue haze around the flowers.

The process takes up to 150 tries to get an image right. He also uses a protective frame of wood around his easel to ensure the flowers are the only things getting electrocuted. And did we mention the whole process is done in complete darkness? We had to talk to Buelteman himself to hear more. Scroll down for a slideshow.

HP: You made 80 photos from 1999-2007, working an average of 60 hours a week. Why have you spent so much time on these electric flowers?

RB: Passion. This work, including the extraordinary challenges faced in the creation of a single successful image calls to me, just as my black-and-white landscape photography did before 1999. What others may regard as hard work, I see as an opportunity for self-expression and contribution.

My photograms are made by using the living plant itself as a filter through which electricity and fiber optically delivered light are passed, leaving the shadow and energy field of the plant exposed on large sheets of color transparency film. With these works I seek to make life itself present, revealing its glory and probing its mystery.

Just as it always has, art waits for those who do the work.

HP: What scientific background did you have prior to embarking on this project?

RB: In contrast to photographers turning to digital technology for new tools to achieve their creative freedom, I turned to simplicity, mindful craftsmanship and the direct exposure of photographic media to find my own. At a time when the photographic community is awash with corporate influence, resulting in a necessary dependence of every photographer on sophisticated proprietary technologies, I sought to make art that reminds us that creativity has no owner.

At present I am a guest of Stanford University at the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve, where I have the privilege of making photographs of the native plants found there. This 1189-acre wonderland provides a natural laboratory for researchers from all over the world. The equipment I have built for making these works is hand-made and in a constant state of evolution as my vision develops. All these images were made without the use of cameras lenses or computers.

HP: Are you making a comment on the relationship between nature and technology, and if so, how?

RB: No. The only commentary I make is contained within the four borders of my prints. While it is currently en vogue for every piece of contemporary art to have an accompanying intellectual dialogue, I allow the work to speak for itself. There is too little attention paid to the immense difference between the world as described and the world as sensed. My art lives in that gap.

HP: Your book 'Signs of Life' is a response to the digitalization of photography. What do you think about the rise of Instagram and other digital platforms?

RB: Having been disabled with Lyme Disease since 2008, I am grateful that people continue to find value in this old world film photographer’s works.

As a life-long resident of Silicon Valley, I find it remarkable that a few lines of code changing a color photo into one with sepia tones could get people so excited. We now live in a country where everyone is a photographer, with all these terrific new ways to share. It is an exciting time, and the cultural impact will be with us for years to come.

See a slideshow of Buelteman's photograms below, and let us know your thoughts in the comments section: