As students return to their campuses, many will be wondering what sort of a job market they will find when they graduate. According to the Confederation of British Industry, recovery hinges on expanding exports. But the UK is being held back by a lack of language skills, crucial to doing business abroad. Lack of linguistic ability is acting as a "tax on UK trade", the CBI concludes.

Yet far from seeing a prioritisation of language learning, the UK is in the throes of a huge linguistic slump as more and more universities are closing their modern language degree courses. That's the stark finding of an exclusive new analysis of Ucas course listings for 1998, 2007 and 2014-15 by Education Guardian.

Whereas in 1998, there were 93 universities offering specialist language degrees, now only 56 do, a 40% drop.

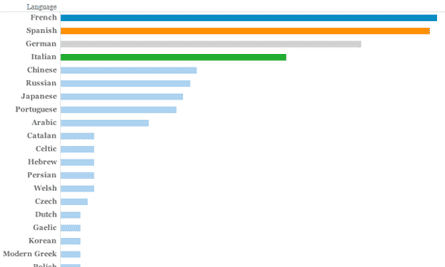

Our analysis shows that over the past 15 years, the number of universities offering German degrees has halved, while there are 40% fewer institutions at which to study French. And what particularly alarms language experts is the speed of decline since 2007. Whereas between 1998 and 2007 there was a 15% drop in French and a 26% decline in German courses, the pace of closures has escalated. There are now 29% fewer universities offering French and German than six years ago and 15% fewer offering Italian. Even Spanish, which held up well between 1998 and 2007, has suffered in recent years. Since 2007, the number of universities offering Spanish degrees has fallen by over a third.

"If this rate of decline continues, two or three language departments will close every year and the remaining students will have a lot less choice, says Michael Kelly, head of modern languages at Southampton University and former adviser to both the coalition and Labour governments. "Universities are finding it difficult to fill their places, and more middle-ranking universities are closing language courses, as well as those post-92 universities that are in a more precarious financial position."

Our findings show that 24 universities have shut all specialist language degrees (straight single honours or joint honours with another language) since our last analysis six years ago. In 2007, data given to Education Guardian by the University and College Union (UCU), based on Ucas figures, already showed a worrying decline in language degrees. But our interactive guide, published on Tuesday, showing all language degrees available in the UK for 2014-15 entry and allowing users to search by language, institution and degree type, reveals that the pace of closures has accelerated.

Since 2007, 11 universities have closed down all language courses entirely, including Anglia Ruskin, Brighton, Liverpool John Moores and Wolverhampton. A further 13 have dropped specialist language degrees but still offer courses combined with another subject, such as physics or management. These include Dundee, Goldsmiths, Greenwich, Kingston, Plymouth and Sheffield Hallam.

And with the announcement in June that all of Salford's highly regarded language courses were going to be cut, experts worry that students seeking the more vocational language degrees, with fewer literature and culture modules and more preparation for jobs, will have fewer and fewer options open to them. "These findings are really worrying as now there is a whole cohort of potential students for whom a language degree may not be an option," says Jim Coleman, chair of the University Council of Modern Languages and professor of language learning and teaching at the Open University.

Teresa Tinsley, a languages consultant and former director of communications at the National Centre for Languages, agrees. "There needs to be choice. We really need to be boosting languages take-up by introducing more variety of courses. But we're not even holding on to what we have, we are going backwards."

Part of the problem is that language departments are often more expensive to run than other subjects. Whereas one history professor could in theory cover for another, a Russian lecturer cannot usually be asked to teach Italian. So languages typically need higher staffing levels. If student numbers fall, it is therefore harder to justify keeping the degree open. "Modern language departments are expensive relative to others because they operate as a conglomeration of small units, each of which needs a certain level of staffing," says Katrin Kohl, a professor of German at Jesus College, Oxford, and director of the Oxford German network. "The fewer students they get, the more that puts pressure on posts and ultimately the viability of the language itself."

Since 2007, Ulster, London Met, Middlesex, Oxford Brookes and Roehampton have dropped single-honours French; five institutions have cut single-honours German degrees (Royal Holloway, Salford, Sussex, Aberystwyth, Queen's University Belfast) and three have cut single-honours Spanish (Middlesex, Sussex, Stirling).

And languages are becoming even more of an elite subject than they already were. Out of remaining single-honours courses, three-quarters of Italian degrees, two-thirds of German and half of French and Spanish studies degrees are taught at Russell Group universities. The dominance of elite universities is particularly acute in Russian, where Central Lancashire is the only post-92 institution to offer the subject and only as a joint-honours degree.

"Language degrees are good for employability, but vocational language degrees are disappearing. People who do not think a Russell Group university is for them are therefore losing out," says Coleman.

But even among the Russell Group, the number of courses is shrinking. Only 12 of the group's institutions still offer single-honours degrees in all four main European languages – French, German, Italian and Spanish. Cambridge and York do not offer any single-honours languages at all – all their language degrees are joint honours.

This dominance by elite universities is creating a vicious circle, says Tinsley. "If all the language courses end up only being in Russell Group universities, then there's no incentive for pupils who aren't going to get into those institutions to take a language at A-level."

Already, language students come disproportionately from affluent backgrounds – one-quarter of undergraduates on language degrees come from independent schools, compared to 11% of the student population as a whole.

This is because at secondary school, language learning is holding up better in fee-charging schools and at state schools in more affluent postcodes. In 2007, 26% of pupils on free school meals took at least one modern foreign language, whereas now only 14% of pupils on free school meals do.

After 2004, when the Labour government dropped languages as a compulsory subject at key stage 4, the proportion of pupils taking a language GCSE plummeted. This year's figures show some recovery. But demand for languages beyond GCSE is falling. Although Spanish is bucking the trend, the number of pupils taking traditional modern foreign languages at A-level is at its lowest since the mid-90s.

Part of the problem could be that it seems harder to get the top grades in languages. Whereas 8.4% of students studying physics, chemistry and biology A-levels achieved an A* this year, only 6.9% taking French, German and Spanish achieved A*. Worried about this attainment gap, Ofqual is conducting an inquiry into how modern language A-levels are marked. But writing in Tuesday's Guardian, academics worry that unless a new marking regime is in place by next year, potential linguists will continue to be put off.

The government has introduced compulsory language lessons in primary school from next year, but universities cannot, of course, expect to see any benefit from this for many years to come.

Although languages have been designated "strategically important and vulnerable subjects" by the Higher Education Funding Council for England since 2005, Hefce is so concerned about the problems that it has announced an extra £3.1m funding for language degree programmes. The Routes into Languages consortium of 80 universities, led by Southampton, is encouraging collaboration between higher education, schools and employers.

Hefce has also, with the research councils, funded language departments to work more closely with other disciplines. And some universities are preparing to bid for Hefce money to develop more vocational language courses to run alongside traditional degrees. "We have really got to keep being innovative," says Charles Forsdick, James Barrow professor of French at Liverpool University.

There are snippets of good news. Entries to GCSE and A-level Chinese are up, as is the number of universities offering that as a subject. Japanese is also holding up well, and Arabic remains stable.

And although specialist language degrees are suffering, joint-honours degrees with a language component, such as law with French, are holding up. The number of students doing beginner and intermediate language modules – not part of main degrees – is increasing. "There are more students studying languages, but not necessarily as their main degree," says Forsdick.

David Willetts, universities minister, says: "The last government marginalised languages in schools. This government is reversing the decline. Language learning at GCSE is now at its highest level for five years. This will flow through to higher education in due course and in the meantime we are giving extra funding to modern foreign languages via Hefce."

But Kelly says ministers need to do much more as a matter of urgency. "The government needs to have a more coherent policy in secondary education," he says. He would like to see languages made compulsory again to age 16 and a wider range of options for studying languages after GCSEs. "We need an education system that is geared to recognise that languages are integral to society and the economy."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion