Earlier this week, musician Neil Young finished raising the third biggest amount ever on crowdfunding website Kickstarter. His Pono music player and downloads store attracted $6.2m of pledges, with plans to launch both later this year.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

Pono unites the two key strands of projects that have been most successful on Kickstarter: art and technology. The site has popularised the idea of crowdfunding, where creators or companies go directly to their existing fans or potential customers and ask them for money in return for the finished product – as well as more rewards for those who choose to pay more.

Kickstarter isn't the only company doing this. It has direct rivals like Indiegogo, area-specific ones like PledgeMusic, Unbound and Distrify (for musicians, authors and filmmakers respectively), and more business-focused companies helping startups raise money like Fundable, Crowdcube and Seedrs. But it's Kickstarter projects that have made the biggest waves so far across a range of industries.

Here are 20 of the most significant projects so far: not just what they raised money for, but what happened next, and what the lessons have been for creators and fans alike.

MUSIC, FILM AND ARTS

Amanda Palmer

What? Musician Amanda Palmer raised $1.2m from 24,883 backers in June 2012 to make a new album and art book, then tour in support of them both. “My first BIG, LEGIT studio album undertaking since breaking from a major label,” as she put it.

What happened next? The album, Theatre is Evil was released in September that year, to appreciative reviews. Palmer set off on tour, but not without controversy. She invited musicians from cities on the tour to back her on-stage in return for beer, high fives or hugs and merchandise, rather than fees. Cue online criticism, which Palmer responded to by promising to pay all the musicians. She'd already broken down in May how the Kickstarter funding would be used, in a blog post showing how she might end up breaking even on the project, thanks to the costs of production and touring.

What did it mean? Relatively few musicians have online fanbases as passionate as Palmer's, but the success of her campaign showed her peers what's possible – while her honesty about the costs involved dissuaded any perceptions that crowdfunding is a route to easy money.

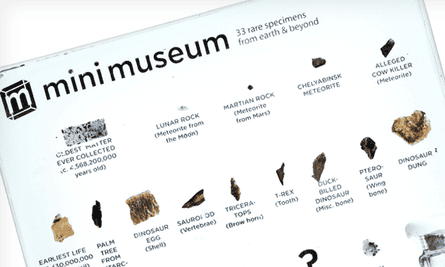

Mini Museum

What? Hans Fex raised $1.2m from 5,030 backers in March this year for his "pocket-sized collection of rare specimens... a portable collection of curiosities where every item is authentic, iconic and labeled". Said items including shards of lunar rock, dinosaur egg-shell, mummy wrap and tiny chunks of London Bridge.

What happened next? Having far exceeded his original goal of $38k, Fex is now working on the initial kits for the Mini Museum, with the first units due to ship in July. He's also launched an official website and mailing list to provide updates on the project's post-funding progress: a reminder that for every successful Kickstarter, the hard work comes after the money is secured, with just as big a need for regular updates on how things are going.

What did it mean? "The universe is amazing," explains Fex on his website. The success of his crowdfunding campaign showed that there are enough people out there who agree to make his lifelong project a reality. It's also likely to serve as inspiration for more popular science projects.

The Veronica Mars Movie Project

What? Writer Rob Thomas raised $5.7m from 91,585 backers in April 2013 to bring back popular TV show Veronica Mars in movie form, becoming the fastest project to reach both $1m and $2m in the process. His aim was to persuade Hollywood studio Warner Bros – which owned the rights – that there'd be demand for the film. "I suppose we could fail in spectacular fashion," wrote Thomas in his pitch. They didn't.

What happened next? With star Kristen Bell already on board, the film was certain to be made as soon as it started breaking crowdfunding records. In March 2014, it was released, and pulled in $2m in box-office receipts in the US alone for its opening weekend. Even more interestingly, though, the film made its debut the same day on Amazon, iTunes and other video-on-demand services. "For a movie to be released in selected theaters in multiple countries and available to rent and purchase and watch on-demand worldwide, all on the same day? It's pretty much unheard of," wrote Thomas.

What did it mean? Veronica Mars is the latest proof that cancelled TV shows with a fervent fanbase can find a new life – something that goes beyond crowdfunding, as Amazon's deal to revive discarded BBC crime drama Ripper Street showed. And the Veronica Mars movie is also part of a wider movement breaking down the barriers between cinematic and digital releases for films.

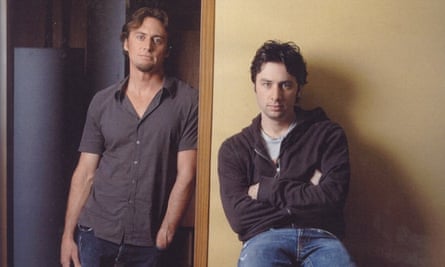

Wish I Was Here

What? Actor, writer and director Zach Braff raised $3.1m from 46,520 backers in May 2013 to make his next film, as an alternative to a traditional financing deal. "It would have involved making a lot of sacrifices I think would have ultimately hurt the film," wrote Braff, citing the success of the Veronica Mars campaign as inspiration.

What happened next? Braff's campaign was controversial while it was still happening, sparking questions online about why he didn't fund the project himself – compounded when it emerged that film financier Worldview Entertainment was topping up the budget. Braff had been open about his intent to raise more money beyond Kickstarter, though. "Nothing about the making of this movie has changed. This movie is happening because backers funded it," he wrote in an update for those backers. Wish I Was Here was praised when it debuted at the Sundance film festival this January, and will go on general release this summer.

What did it mean? More evidence that for bigger projects, Kickstarter complements traditional film financing rather than replacing it altogether. Braff's project also shed more light on the tension that can surround crowdfunding by celebrities, who some fans may assume are richer than they actually are.

The Newest Hottest Spike Lee Joint

What? Veteran filmmaker Spike Lee raised $1.4m from 6,421 backers in August 2013 to make his next, unnamed film. He stressed his independent credentials in an effort to head off the kind of criticism levelled at Zach Braff. "The truth is I’ve been doing KICKSTARTER before there was KICKSTARTER, there was no Internet," wrote Lee. "Social Media was writing letters, making phone calls, beating the bushes. I’m now using TECHNOLOGY with what I’ve been doing." The film itself is a thriller. "These people are ADDICTED to BLOOD. Yet however they are not VAMPIRES. It’s going to be SEXY, HUMOROUS and BLOODY. To me that’s a unique combination."

What happened next? Lee hit his target and got to work on the film, having confirmed actors Stephen Tyrone Williams, Zaraah Abrahams and Michael K. Williams in lead roles. Recent updates reveal he's been sifting through submitted music from unsigned artists while signing up Bruce Hornsby to record the score.

What did it mean? Lee's campaign showed the importance for famous creators of explaining why they need the money and what they plan to do with it – although it also proved you can keep most of a film's plot and themes up your sleeves without putting off potential backers.

Video Game High School: Season Two

What? Video Game High School isn't a film: it's a web series made for YouTube by RocketJump, the company of YouTube star Freddie Wong. RocketJump raised $808k from 10,613 backers in February 2013 to make the show's second series. It's set in an alternate universe where video games are the "biggest spectator sport in the world", complete with a gaming academy: "Think Hogwarts, but instead of spells and magic wands, it's headshots and IBM Model M keyboards!" The campaign followed a successful Kickstarter for the first series in 2010, which went on to notch up 40m views online.

What happened next? The second season of Video Game High School's six episodes have been watched nearly 19m times on YouTube so far, and series three is already in production. The multi-channel network (MCN) that backed it, Collective Digital Studio, was at the recent MIPTV television industry conference trying to sell the seasons to broadcasters as a package to show on regular TV. But the show has also brought Wong to the attention of bigger beasts in the media world: RocketJump has just signed a partnership deal with Hollywood studio Lionsgate to work on new formats.

What did it mean? YouTubers and MCNs have lots of ambitious ideas to make shows for online viewing, but concerns about how to turn a profit while bumping up the production values. RocketJump's Kickstarter showed that the keen fanbases for the best online talent can help to boost budgets.

Marina Abramovic Institute

What? Performance artist Marina Abramovic raised $661k from 4,765 backers in August 2013 to help her found the Marina Abramovic Institute: a building and body "dedicated to the presentation and preservation of long durational work, including that of performance art, dance, theatre, film, music, opera, and other forms that may develop in the future". The entire project will cost $20m, with Abramovic having coughed up $950k to buy the building before turning to Kickstarter to fund phase one of its design. "With your contribution, you become a founder of the institute not only financially, but also conceptually," she explained.

What happened next? Funding secured, work on the Institute has pressed on: this month, an update revealed plans for the various rewards that backers had stumped up for, while Abramovic has also been running live streams teaching some of her "Abramovic Method exercises" via video. She has also launched MAI Hudson, a website designed to house "immaterial and long durational works" as well as a series of her exercises.

What did it mean? A reminder that the arts on Kickstarter aren't just about music, films and games. Oh, and also a lesson that Lady Gaga practising your exercises in her birthday suit is a handy publicity boost for a crowdfunding project as it enters its crucial stages.

TECHNOLOGY

Pebble

What? Described at the time as an "E-Paper Watch", Pebble raised $10.3m from 68,929 backers in May 2012, making it the most popular Kickstarter campaign ever. Most people now would describe it as a smartwatch – a category that's now attracting firm attention from the likes of Samsung, Google and Apple, but which back then still felt a bit... science fiction. Still, Pebble appealed to plenty of people with its promise of a "customisable" watch that could run apps, show notifications from a paired smartphone, and work with other accessories including fitness devices.

What happened next? The first Pebble units were due to ship to backers in September 2012, but the company missed this deadline, eventually starting to ship in January 2013. Since then, Pebble has done well: the company shifted 400,000 units by March 2014, by which point its second-generation model – the Pebble Steel – had been released. The company has also just launched its own app store for smartwatch apps on both iOS and Android, providing an easy way for owners to find what's available for Pebble.

What did it mean? Pebble remains the most successful (in terms of raising money, at least) Kickstarter project ever: it proved that hardware ideas that had failed to float venture capital firms' boats could find another route to market – and Pebble was later able to raise some VC cash on the back of its Kickstarter popularity. But Pebble has also taught other startups about the potential delays when your crowdfunding is more popular than you expected.

Ouya

What? Fledgling console maker Ouya raised $8.6m from 63,416 backers in August 2012 for its Android-based 'microconsole', with the promise of an open, hackable device with a healthy catalogue of indie games – all available in at least a basic version for free. The company pitched itself as the antidote to traditional console bloat: "It's time we brought back innovation, experimentation, and creativity to the big screen," as its Kickstarter pitch put it. "Let’s make the games less expensive to make, and less expensive to buy." The idea being to bring the aesthetics and business models of mobile games to the TV in your living room.

What happened next? Ouya managed to hit its shipping targets... sort of. The first consoles left its production lines in March 2013, although not every early backer got their unit that month, sparking complaints online. Out of the box, the console was okay: simple to set up and with plenty of games, but a mixed bag in terms of quality – and with a below-par controller compared to rival consoles. Armed with another round of VC funding (just like Pebble) Ouya proceeded to put its console on general sale in June 2013, and has worked hard on improving its software and catalogue since – although not without controversy in the case of its attempt to fund exclusive games by matching developers' own Kickstarter campaigns. In 2014, though, Ouya appears to be shifting from a device into a software platform for others to use – for example, embedding it in TVs.

What did it mean? When Ouya's crowdfunding campaign ended, it seemed to herald a bright future for microconsoles. Since then, several have been launched, and none appear to have sold that well – certainly not in numbers great enough to trouble Sony, Microsoft or Nintendo. Even so, Ouya provided a template – a flawed one, arguably – that's now being built on by the likes of Amazon (with its Fire TV) and perhaps Google and Apple in the months to come.

Oculus Rift

What? Virtual reality (VR) startup Oculus Rift raised $2.4m from 9,522 backers in September 2012 – a storming year for big hardware projects on Kickstarter. It was raising money to develop a VR headset for gaming, with developers the key target for its campaign: they could pledge to get early access to the Oculus Rift developer kit. The helmet promised to finally deliver on the past hype around VR. "With an incredibly wide field of view, high resolution display, and ultra-low latency head tracking, the Rift provides a truly immersive experience that allows you to step inside your favorite game and explore new worlds like never before," as the company put it.

What happened next? Post-Kickstarter, the first devkits went out, and developers started hacking with Oculus Rift to make existing games work for it, as well as creating some new made-for-VR experiences. The buzz gradually built – hiring Doom co-creator John Carmack as chief technology officer in August 2013 didn't hurt in that regard – and by the Game Developers Conference in March 2014, Oculus was showing off the second edition of its devkit, with improved features. Then, a week later, social network Facebook shocked the games and tech industries by agreeing to pay $2bn to acquire Oculus Rift, promising to take it beyond gaming. "Oculus has the chance to create the most social platform ever, and change the way we work, play and communicate," said CEO Mark Zuckerberg, although there was a predictable backlash from some gamers and developers about the new owner.

What did it mean? Virtual reality has a chequered history of overhype and underwhelming... reality, for want of a better word. For Oculus Rift, crowdfunding was the springboard to giving the technology credibility again – as well as to further funding from venture capital firms in 2013, just like Pebble and Ouya. Besides pricking up Zuckerberg's ears, Oculus Rift was also a factor in Sony pursuing its own VR ambitions: unveiled at GDC with its Project Morpheus.

3Doodler

What? "It's a pen that can draw in the air!" chirped the Kickstarter pitch for 3Doodler, which raised $2.3m from 26,457 backers in March 2013. "3Doodler is the 3D printing pen you can hold in your hand. Lift your imagination off the page," it continued, with the obligatory-in-3D-printing-circles shots of a plasticky Eiffel Tower. The device promised ultra-simple usability: in theory, you'd just plug it into a power socket, then start scribbling something you wanted to print in the air, with the heated plastic cooling into something solid.

What happened next? The company fulfilled its promise to ship 3Doodlers to all its backers by March 2014 – in fact, it hit the target a month early. It's also created a community for those early buyers, providing stencils, videos and images to spark their inspiration when they get hands on with the printing pen. 3Doodler has also announced plans to start selling the device more generally – in the UK, Maplin has bagged an exclusive on it, and will start selling 3Doodler in its stores on 20 April.

What did it mean? 3Doodler isn't a desktop 3D printer, but its Kickstarter campaign paved the way for some of those to take funding from the crowd too: Form 1 (see below), Robox and the still-raising Micro being successful examples. At £100, too, 3Doodler may well be many people's first hands-on experience of 3D printing.

Arkyd

What? "A space telescope for everyone," according to the Kickstarter listing for this project. Planetary Resources raised $1.5m from 17,614 backers in July 2013 for its ambitious plans to create "the first publicly accessible space telescope", which people will be able to take control of and watch objects in space – as well as taking photos of the Earth (aka particularly-showoff selfies). The company was developing the telescope itself, but turned to Kickstarter to raise money to launch and support it, as well as creating the necessary controls to help people control it.

What happened next? Work continues apace on Arkyd, with semi-regular updates keeping backers informed of the project's progress. In December, for example, the company showed off its "Beta-Selfie Cam", while continuing to send out rewards to the various tiers of pledgers. It's also working with a company called Zooniverse on a project called Asteroid Zoo, which aims to help people spot asteroids from their desktops. But Arkyd is just one of Planetary Resources' aims: it was originally a spin-off from the company's main ambition: "to build technology enabling us to prospect and mine asteroids".

What did it mean? Here as in other cases, from films to gadgets, the money raised on Kickstarter wasn't the whole story – it provided important publicity for the overall project. But it also hinted at the potential for space science projects to find audiences and funding from people enthralled by their potential. Organisations like Nasa are exploring the potential of crowdsourcing – not necessarily funding – in parallel.

The Dash

What? Hardware firm Bragi raised $3.4m in March 2014 from 15,998 backers for its wireless smart headphones: small earbuds that stream music from a nearby device over Bluetooth, but which also have their own built-in 4GB music player. The Dash is also a fitness-tracking gadget though: recording your steps, pace, distance, heart rate and other stats as you go about your business. It works as a Bluetooth headset for voice calls too, with an ear-bone microphone.

What happened next? It's only a fortnight since the Kickstarter campaign ended, so not much has happened yet: people who paid for the developer packages will get prototype devices in July so they can start making apps that work with The Dash, but regular pledgers will get start getting theirs in November if Bragi hits its deadlines.

What did it mean? The latest wearable gadget to cause a stir, with the crowdfunding buzz a key factor in The Dash's rise to prominence. Expect more of these kinds of gadgets to follow, with the crossover between music and fitness likely to be a fertile one for hardware startups.

Kano

What? Kano raised $1.5m from 13,387 backers in December 2013 for its "computer and coding kit for all ages", with its guts consisting of a Raspberry Pi computer. Kano provided the case, a keyboard, speaker and wireless server, along with software aimed at encouraging children to learn programming skills – the Kano Blocks coding language. "We designed the Kano Kit to be a bit like our favorite boardgames growing up. It's vibrant, repackable, and doesn't take itself too seriously," the UK-based startup explained.

What happened next? Again, it's early days: Kano is planning to ship its first kits in June, so for now the company is beavering away getting its product ready. It's clearly confident though: it's also accepting pre-orders on its website for the £99 kit to ship in July. Kano has also been engaging with early adopters who are keen to explore its Kano OS software, making it available in beta form to install on Raspberry Pis. Kano has also been getting involved in the British government's Year of Code scheme, which is hoping to get people of all ages exploring programming.

What did it mean? Kano was just one of a number of crowdfunding campaigns for technology aiming to get kids coding: see also Play-i, Primo, Hello Ruby, Robot Turtles and ScratchJr in the link above. All of these showed there's a sizeable community out there of parents and/or tech industry folk willing to get their wallets out for innovative projects in this area.

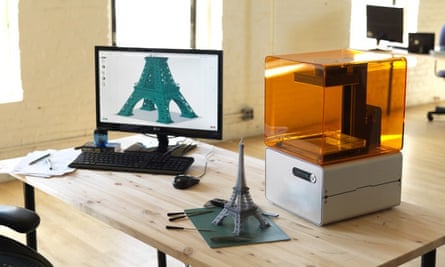

Form 1

What? Another attempt to bring 3D printing to the crowd, this time from a company called Formlabs. It raised $2.9m in October 2012 to help make an "affordable, high-resolution 3D printer for professional creators" – although in this case, affordabl meant $2,299 for the earliest backers, rising to $2,699 for latecomers. "Our reason for starting this project is simple: there are no low-cost 3D printers that meet the quality standards of the professional designer," the company explained at the time, flagging up its use of "stereolithography" techniques to produce better-quality 3D prints.

What happened next? After the success, came the patent row: in November 2012 another 3D printing firm – 3D Systems – sued Formlabs AND Kickstarter for patent infringement over that use of stereolithography. By June 2013 Formlabs and 3D Systems were reportedly in settlement talks over the lawsuit, which was dismissed later that year only for 3D Systems to sue over eight more patents, albeit without including Kickstarter this time. Still, the Form 1 remains on sale, and has been reviewed approvingly for its detail, ease of use and quiet operation.

What did it mean? Another sign that 3D printing is an area ripe for crowdfunding. Although Form 1 also showed that successful Kickstarters can also bring startups to the attention of bigger companies in the industries they're trying to disrupt – it certainly won't be the last Kickstarter-triggered patent dispute.

GAMING

Project Eternity

What? Developer Obsidian Entertainment raised just under $4m from 73,986 backers in October 2012 to make Project Eternity: “an isometric, party-based computer RPG set in a new fantasy world”. It promised to draw on a series of classic games worked on by the team for inspiration: “Take the central hero, memorable companions and the epic exploration of Baldur’s Gate, add in the fun, intense combat and dungeon diving of Icewind Dale, and tie it all together with the emotional writing and mature thematic exploration of Planescape: Torment”.

What happened next? When the Kickstarter closed, Obsidian was aiming for an April 2014 release for Project Eternity. The game has since been renamed Pillars of Eternity, and in March 2014 the developer announced a publishing deal with Paradox Interactive, which will help out on marketing and distribution. The game isn’t hitting its shipment deadline, but Obsidian says it’ll be out “this year”. Backers have received regular updates on its progress.

What did it mean? The latest news is a reminder that while crowdfunding can give developers the resources to make and release a game alone, that doesn’t mean a publisher won’t come in handy later. “By handing off duties not related to development, Obsidian can focus on making the game that much better,” claims the company’s FAQ article for its publishing deal.

Torment: Tides of Numenera

What? Developer inXile Entertainment raised $4.2m from 74,405 backers in April 2013 to make Torment: an RPG set in the world of Numenera – a tabletop roleplaying game created by Monte Cook that was itself funded by a Kickstarter campaign the year before. "With Torment, we're striving to create a rich role-playing experience that explores similar deep, personal themes," explained the company in its pitch.

What happened next? Whereas crowdfunded gadgets tend to ship within a year of their campaigns, more complex games have longer production processes: inXile's team has been providing regular updates on the design process for Torment, with full production about to kick off. The company is also working with Obsidian Entertainment (see above) to license the technology from Pillars of Eternity. "It provides us with a stronger starting point for certain game systems and pipelines," explained inXile in a message to backers. "This means we will have more resources to invest on other aspects of the game, allowing us to achieve a higher quality overall."

What did it mean? Like all the games in this section, the most interesting aspects of their crowdfunding campaigns were the insights into the development process provided by the updates for backers: the commitment to openness when a game is funded by the crowd is valuable on that score alone.

Double Fine Adventure

What? Developer Double Fine raised $3.3m from 87,142 backers in March 2012, so for a long time, this was the most high-profile example of a game getting funded on Kickstarter. Double Fine promised a "classic point-and-click adventure" from a team headed by Tim Schafer, whose career included co-designing classics of the genre The Secret of Monkey Island and Day of the Tentacle. The theory: there was still lots of demand for the genre among players, but lukewarm interest from publishers. Kickstarter provided a way to cut out the middleman and prove whether that theory was true.

What happened next? Double Fine Adventure hit its $400,000 target in just eight hours, stirring up a swarm of interest within the games industry and beyond. The game has since been renamed Broken Age, and is being filmed for a companion documentary series about its development. However, the original ambition to develop the game in 6-8 months has proved to be a drastic underestimate. "It’s just taking a while because I designed too much game, as I pretty much always do," explained Schafer in an update for backers in July 2013, outlining plans to split it in two, releasing the first half in January 2014. Act 1 was duly released then, with sales funding Act 2 to follow later this year.

What did it mean? Pulling in lots of money from Kickstarter doesn't help you make a game faster: in fact, it may fuel the kind of creative ambitions that lengthen the development process considerably. Schafer has been open about the hard decisions along the way. "If you take money from a publisher, it's a contract you fulfill or they'll sue you. Here it was just a moral contract with the backers to do right by them, and that felt in some ways a lot stronger," he said in February.

Penny Arcade

What? Game-slanted comic strips site Penny Arcade raised $528k from 9,069 backers in August 2012 to remove ads from its website, with a Penny Arcade Sells Out campaign. "People often want to know how they can support the site in a way that doesn't involve t-shirts or looking at advertising, and I think we may have a way. What I'm saying is that we want to sell out, and we would love to sell out to you," explained its pitch.

What happened next? They sold out, and Penny Arcade's homepage was redesigned to be ad-free. Surpassing its initial funding target also financed new projects, including its "reality game show for web cartoonists" Strip Search. In 2014, though, ads are coming back to the site. "It’s not something most people even care about, and I can pay salaries with it," explained the site, while relaunching a subscription-based "Club PA" option for people who wanted to stay ad-free.

What did it mean? A lot of independent websites are grappling with the economics of online publishing, from making advertising pay to the possibility of subscriptions. Penny Arcade's Kickstarter was valuable in showing one possible alternative, but also in starting a longer-term conversation about the value of ads.

CLOTHING DAVID CAMERON WOULD LOVE TO HUG

The 10-Year Hoodie

What? Flint and Tinder raised $1.1m from 9,226 backers in April 2013 for its 10-Year Hoodie, which does exactly what it says on the tin: a hooded sweatshirt that lasts for 10 years. Well, obviously it's too early to tell if it follows through on that promise... Made in the US and with the promise that the company would mend any rips and tears. "It's more than a sweatshirt though; it's a battle cry. Not everything should be disposable," it claimed.

What happened next? A year on, the 10-Year Hoodie is available to buy for anyone from Flint and Tinder's website in a range of colours, costing $99.50. And the experience was clearly so happy for the company, it's having a second bite at the Kickstarter cherry with something called Denim on Demand: jeans made to measure for $89 a pair, in a campaign that raised $325k after an initial target of $75k.

What did it mean? A sign of the potential of crowdfunding for clothing, not just tech and arts. And also a hint of the strength of features like local manufacturing and durability, especially when going direct to customers can help bring the costs down.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion