Why Nobody Writes About Popular TV Shows

The Faustian Bargain of Television: Be widely watched and scarcely acknowledged, or be widely praised and scarcely watched

On TV, the concept of "popularity" is easy to measure and hard to understand.

In music, the most popular songs are inescapable, and their artists become national celebrities. In movies, the most popular films are feted in the Monday papers and widely acknowledged, even if they only compete for the special-effects awards in March. But on television, the world of criticism and the world of viewership aren't merely askew; they're mostly on different planets. No self-respecting TV critic writes about NCIS: Los Angeles, ever—ever—even though the all-time most-popular episode of Game of Thrones (which is, itself, the all-time most-popular HBO show) got fewer viewers than an NCIS: LA rerun. As I wrote a few months ago, the most essayed-about show (Girls), most tweeted-about show (Pretty Little Liars), and most buzzed-about show (at the time: House of Cards) sum to half the average audience of NCIS (which is hardly essayed, tweeted, or buzzed about at all).

More than other entertainment industries, TV seems to play by the rules of a peculiar Faustian bargain: Be popular and scarcely acknowledged; or be praised and scarcely watched.

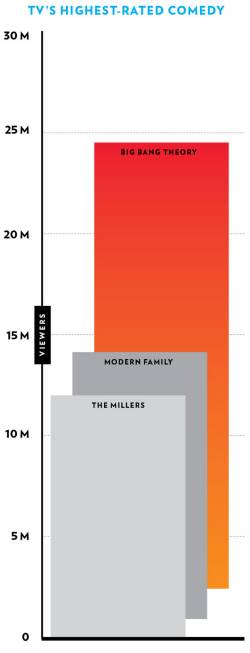

This bring us to The Big Bang Theory, which deserves a theory of its own. The Big Bang Theory is not merely the most popular comedy on television, besting its nearest rival by a margin of 10 million viewers. It's the most popular comedy for every demographic between the ages of 12 and 54 and, more importantly, the most popular show on television in 2014. An estimated 84 million people—equal to the combined populations of California, Texas, and New York—have watched at least six minutes of it this year, according to a marvelous new investigation of the show's popularity in New York magazine.

Not unlike the big bang, itself, a good theory for what makes the TBBT so astonishingly successful requires empirical evidence, but ultimately its full explication is, perhaps, beyond the limits of human knowledge. On the empirical side of things, there are four key factors: Chuck Lorre + CBS + Thursday + Syndication. That is: Take a formula-driven buddy comedy by an experienced showrunner with a proven meta-script (put average guys in awkward situations and add lite-raunchy humor), add the power of a CBS audience (it's by far the most successful programmer among the networks), give it a Thursday-night slot, and finish with the redoubling effect of heavy syndication on TBS. On the less-empirical side of things, people seem to find this show really funny.

So why doesn't popularity demonstrated by CBS's formidable line-up translate into much attention from the press, which in many industries (entertainment, politics, sports) covers what is popular simply because it's popular?

There's a shallow and deep explanation. The shallow explanation is that TV I (and perhaps you) live in the cloistered monastery of media. Television criticism thrives with unpacking precisely the sort of shows that don't appeal to a mass audience, because they weren't made for a mass audience.

Which leads to the deeper, economic explanation. Broadcast TV sells audiences. Premium TV sells a "brand." That's how HBO's Richard Plepler, speaking yesterday at The Atlantic's New York Ideas conference, summed up the difference between what he does and what broadcast television—e.g.: NBC, ABC, CBS, FOX—tries to do. HBO makes all of its money from selling subscriptions (to the HBO channel) and selling shows (e.g. to Amazon and anybody else). Broadcast television, however, has an entirely different business model based overwhelmingly on advertising. Among the broadcasters, ad money follows audience.

The macroeconomics of TV aren't invisible to consumers. They are incredibly visible. You see them every night. HBO can afford to produce risky niche entertainment because its success is determined, not by maximizing the ratings for each show, but by making just enough original programming that keeps its subscribers from canceling. If a significant share of HBO's audience only watches one show a season (say: Veep), that would be a triumph. If a significant share of CBS's audience only watched 30 minutes of CBS a week, it would be an unmitigated disaster. HBO is hunting sign-ups, so it can afford to downplay ratings. CBS is hunting eyeballs, so it can't. And so CBS and HBO can both be thrillingly successful on their own terms, even though one channel makes formulaic popular stuff that nobody writes about and the other channel makes much less popular stuff that absorbs the attention of TV media precisely because it isn't formulaic.

In short: TV critics are drawn to writing about creative departures from the very popular formulas that are often required the keep an ad-supported audience tuned into broadcast TV. And so, two different business models in the TV bundle—ad-supported on broadcast vs. subscriber-supported on cable and premium—yield two different worlds: One where lots of people watch TV and one where a handful of people watch and read about it.

***

Update

In the course of writing this piece, it evolved somewhat accidentally from a "here, I'll contextualize a data point with a bit of media economics" into something that looks like a general theory of TV. I bit off more than I was prepared to chew, so I'm going to jump back in here to make some clarifications.

First, HBO and premium cable aren't the only channels making their living with subscribers rather than advertisers. Many cable networks with advertisers, including AMC and FX, make more of their money from subscription fees than ads. This insulates them from the pressure of creating mass entertainment based on reliably formulaic shows. It is not a coincidence that they also happen to produce a higher share of award-winning shows.

Second, I am not saying that all popular TV is ignored by all TV criticism, a absurd position that would require (for starters) that I read literally all TV journalism on the Internet. My thesis is less dramatic: The economic structure of cable channels, which receive most of their money from fees rather than ads, greatly relieves them of the burden of maximizing audience–and as a result they produce television that is less formulaic, more attractive to the writing-and-reading-about-TV crowd, but often less watched.

Here's a list of the most-popular shows on broadcast TV from the end of last year. Clearly shows like The Good Wife, Scandal, Parenthood, Community, and Parks and Recreation receive a certain amount of media attention these days. But they are far from the most popular shows on broadcast. They rank 27th, 44th, 57th, 123rd, and 111st among primetime series in the 2012-2013 season by viewers. The shows ranked immediately behind them were Survivor: Caramoan, The Middle, Private Practice, Guys With Kids, and 1600 Penn. (How I Met Your Mother, which ended this year to lots of fanfare, finished behind 40 shows among 2013 viewers.) Although they might command high ad rates because of the quality or relative youth of their audience, they are not driving much audience, relative to their competition. So even when we restrict our analysis to just broadcast TV, the most-watched shows aren't the most-written about.